Use of honey of Apis mellifera on base agar to differentiate bacterial strains with oxidative-fermenting characteristic

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.30827/ars.v60i2.8682Keywords:

Apis mellifera, honey, carbohydrate oxidation, carbohydrate fermentationAbstract

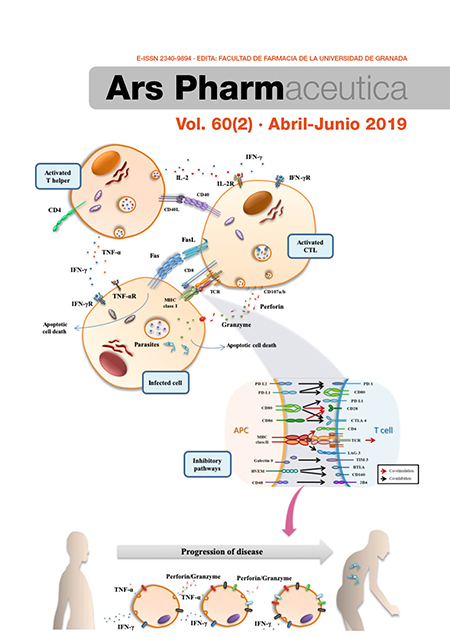

Objective: To evaluate the use of Apis mellifera (honey) on base agar as an oxidant-carbohydrate fermentor differentiator in strains of Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 29212.

Methods: Preliminary phytochemical screening of honey was carried out. Using agar with bee honey as an oxidative-fermenter differentiator, use 96 culture tubes containing 10 ml of randomized base agar and divided into four groups of 24 tubes: group I base agar with honey and Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, group II agar base with honey and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 29212, group III agar OF (basal medium according to Hugh and Leifson, Merck) with Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, and group IV agar OF with Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 29212; being the standard OF agar. Two evaluation criteria were considered: Oxidation and Fermentation of carbohydrates.

Results: Bee honey has alkaloids, triterpenoids and phenolic compounds. The qualifier of Good (100%) was determined for the grip with honey and Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, and agar with honey and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 29212; compared with the agar OF.

Conclusion: The use of agar with honey of Apis mellifera has been shown as good as an alternative to agar OF (Basal medium according to Hugh and Leifson) to differentiate Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 29212 as oxidants and carbohydrate fermentors.

Downloads

References

Cabrera L, Ojeda G, Céspedes E, Colina A. Actividad antibacteriana de miel de abejas multiflorales (Apis mellifera Scutellata) de cuatro zonas apícolas del Estado Zulia, Venezuela. Rev Cient. 2003; 13(3): 205-211.

Ulloa J, Mondragón P, Rodríguez R, Reséndiz J, Ulloa P. La miel de abeja y su importancia. Revista Fuente. 2010; 2(4): 11-18.

Bradbear N. La apicultura y los medios de vida sostenible. Folleto de la FAO sobre diversificación 1. 2005, Roma.

Swallow K, Low N. Analysis and quantitation of the carbohydrates in honey using high-performance liquid chromatography. J Agric Food Chem. 1990; 38(9): 1828-1832. DOI: 10.1021/jf00099a009

Missio P, Gauche C, Gonzaga L, Oliveira A. Honey: chemical composition, stability and authenticity. Food Chemistry. 2016; 196: 309-323. Doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.09.051.

Qiu P, Ding H, Tang Y, Xu R. Determination of chemical composition of commercial honey by near infrared spectroscopy. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1999; 47(7): 2760-2765. DOI: 10.1021 / jf9811368

Vega C, Gutiérrez C, Díaz C. Actividad antimicrobiana de mieles de Apis mellifera de la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia. Rev Fac Nal Agr. 2014; 67(2): 743-745.

San José J, San José M. La miel como antibiótico tópico en las úlceras por presión. Actualización. Medicina Naturista. 2015; 9(2): 93-102.

Koneman E, Allen S, Janda W, Schreckenberger P, Winn W. Diagnóstico Microbiológico. Texto y atlas color. 6 ed. Buenos Aires: Médica Panamericana; 2006.

Welch D, Muszynski M, Pai C, et al. Selective and differential medium for recovery of Pseudomonas cepacia from the respiratory tracts of patients with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Micobiol. 1987; 25: 1730-1734.

Murray R, Patrick S. Microbiología Médica. 6a ed. Barcelona: Editorial Elsevier; 2006.

Tortora F. Introducción a la Microbiología. 9a ed. Buenos Aires: Editorial Médica Panamericana; 2007.

Parés R, Juárez A. Bioquímica de los Microorganismos. 1a ed. Barcelona: Editorial Reverté S.A.; 2012.

MacFaddin J. Pruebas bioquímicas para la identificación de bacterias de importancia clínica. 3a ed. Madrid: Editorial Médica Panamericana; 2003.

Prescott L, Harley J, Klein D. Microbiología. 5a ed. Madrid: Editorial McGraw-Hill; 2004.

Nelson D, Cox M. Lehninger Principios de Bioquímica. 5a ed. Barcelona: Editorial Omega S.A.; 2009.

Ryan K, Ray C. Sherris Microbiología Médica. 5a ed. México: Editorial McGraw-Hill Interamericana; 2011.

Costin I. An outline for the biochemical identification of aerobic and facultatively anaerobic gram-negative rods of medical interest. 5. Intern. Kongr. f. Chemotherapie Wien, B2/1. 1967: 73-76.

Hugh R, Leifson E. The taxonomic significance of fermentative versus oxidative metabolism of carbohydrates by various gram-negative bacteria. J Bact 1953; 66: 24-26.

Lock O. Investigación fitoquímica. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. Lima, 1994.

Kuklinski C. Farmacognosia: Estudio de las drogas y sustancias medicamentosas de origen natural. 1a ed. Barcelona: Editorial Omega S.A; 2000.

Organización Mundial de la Salud. Manual de Bioseguridad en el Laboratorio. 3a ed. Ginebra: OMS; 2005.

Ministerio de Agricultura y Riego. [Internet]. Plan Nacional de Desarrollo Apícola 2015-2025. [actualizado 07 febrero 2019; citado 07 febrero 2019]. Disponible: https://bit.ly/2DXZ5ew

Parra G, Gonzáles V. Las abejas silvestres de Colombia: Por qué y como conservarlas. Acta Biológica Colombiana. 2000; 5(1): 5-37. DOI: 10.15446/abc

Sherlock O, Dolan A, Athman R, et al. Comparison of the antimicrobial activity of Ulmo honey from Chile and Manuka honey against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2010; 10(1): 47. DOI: 10.1186 / 1472-6882-10-47

Montenegro G, Salas F, Peña RC, Pizarro R. Actividad antibacteriana y antifúngica de mieles monoflorales de Quillaja saponaria, especie endémica de Chile. Phyton. 2009; 78(2): 141-146.

Mandal S, DebMandal M, Kumar N, Saha K. Antibacterial activity of honey againts clinical isolates of Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa anda Salmonella entérica serovar Typhi. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine. 2010; 3(12): 961-964. DOI: 10.1016 / S1995-7645 (11) 60009-6

Hermosín I, Chicón R, Cabezudo M. Free amino acid composition and botanical origino f honey. Food Chemistry. 2003; 83(2): 263-268. DOI: 10.1016 / S0308-8146 (03) 00089-X

Wilkinson J, Cavanagh H. Antibacterial activity of 13 honeys against Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Med Food. 2005; 8(1): 100-103. DOI: 10.1089 / jmf.2005.8.100

Gómez C, Palma S. Libro Blanco del Azúcar. 1a ed. Madrid: Editores Médicos; 2013.

Hurtta M, Pitkänen I, Knuutinen J. Melting behaviour of D-sucrose, D-glucose and D-fructose. Carbohydr Res. 2004; 339(13): 2267-73. Doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2004.06.022

Lee JW, Thomas LC, Schmidt SJ. Can the thermodynamic melting temperatura of sucrose, glucosa, and fructose be measured using rapid-scanning differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)?. J Agric Food Chem. 2011; 59(7): 3306-10. DOI: 10.1021/jf104852u

Pigman W, Wolfrom M. Advances in Carbohydrate Chemistry. Volume 4. New York: Academic Press Inc; 1949.

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2019 Héctor Vilchez Cáceda, Miguel Angel Inocente Camones, Luis Cervantes Ganoza

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The articles, which are published in this journal, are subject to the following terms in relation to the rights of patrimonial or exploitation:

- The authors will keep their copyright and guarantee to the journal the right of first publication of their work, which will be distributed with a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 license that allows third parties to reuse the work whenever its author, quote the original source and do not make commercial use of it.

b. The authors may adopt other non-exclusive licensing agreements for the distribution of the published version of the work (e.g., deposit it in an institutional telematic file or publish it in a monographic volume) provided that the original source of its publication is indicated.

c. Authors are allowed and advised to disseminate their work through the Internet (e.g. in institutional repositories or on their website) before and during the submission process, which can produce interesting exchanges and increase citations of the published work. (See The effect of open access).