Multilingual Crowdsourcing Motivation on Global Social Media. Case Study: TED OTP

Lidia Cámara de la Fuente

lidia.camara@uni-koeln.de

University of Cologne

Recibido: 12/01/2014 | Revisado: 2/04/2014 | Aceptado: 23/07/2014

Abstract

Crowdsourcing has emerged in recent year as a new form of volunteering activity. The distributed nature of online volunteers enabled global organizations to mobilize talents from around the world. In this spirit, the past decade has witnessed a vibrant expansion of intercultural virtual collaborative efforts within the crowdsourced audiovisual translation communities.

The aim of our work is to characterise key motivational factors driving volunteer translators to engage in these intercultural collaboration endeavours within one of those virtual communities. As a case in point, TED1 will be studied, a global communication platform where people from all over the world interact with each other creating, sharing, exchanging and commenting on content within a virtual community and several networks.

At TED unpaid volunteers translate audiovisual content into 100 languages, within the framework of an online translation project: the Open Translation Project, hereinafter referred to as OTP.

This paper uses a survey method in which 177 OTP participants responded. They range across 35 different languages and are geographically distributed over four continents, to pinpoint key motivation factors for becoming volunteer translators.

Keywords: Audiovisual Translation, Informal Learning, Intercultural Competences, Online Volunteering, Subtitling

Resumen

El crowdsourcing es una tendencia creciente que ha surgido en los últimos años como una nueva forma de actividad voluntaria. La naturaleza distribuida de los voluntarios en línea a nivel global ha posibilitado a organizaciones de ámbito global a movilizar a personas de todo el mundo. Con este ánimo, la última década ha sido testigo de una vibrante expansión de los esfuerzos de colaboración virtuales interculturales dentro de las comunidades de traducción audiovisual.

El objetivo de nuestro trabajo es caracterizar los factores motivacionales clave que impulsan a las personas a traducir de forma voluntaria y a participar en los esfuerzos de colaboración intercultural dentro de comunidades virtuales. Como ejemplo de ello, aquí se analiza la comunidad TED, una plataforma de comunicación global en el que la gente de todo el mundo interactúan creando, compartiendo, intercambiando y comentando contenidos dentro de la propia comunidad virtual y de varias redes.

En TED en el marco de un subproyecto de traducción en línea, el Open Translation Project, denominado en lo sucesivo OTP, voluntarios traducen contenidos audiovisuales a 100 idiomas.

Para identificar los factores clave de motivación que les llevan a convertirse en traductores voluntarios, se llevó a cabo un estudio compuesto de 177 participantes de TED OTP que representan en su conjunto 35 idiomas diferentes y que se distribuyen geográficamente en cuatro continentes.

Palabras clave: traducción audiovisual, aprendizaje informal, competencias interculturales, voluntariado en línea, subtitulación

1. Introduction

The ever-increasing presence of online collaborative software that enables online audiovisual translation has attracted a growing number of people to translating and subtitling multimedia without getting paid. Collaborative tools supporting online audiovisual translation in real time are proliferating, and other collaborative tools such as Wikis offer collaborative writing sites that facilitate the translation of text as opposed to subtitles (e.g. Wikipedia). But even before the development of such targeted volunteer translator tools, there were - and are - people who heeded the call for volunteer translations. This act of taking a job [albeit volunteer work, or paid work] … traditionally performed by a designated agent (usually an employee) and outsourcing it to an undefined, generally large group of people in the form of an open call is known as crowdsourcing (Howe, 2008). In other words crowdsourcing is a form of outsourcing, one that specifically employs a crowd.

Crowdsourcing is a type of virtual participative online collaboration, which an individual, an institution, a non-profit organization, or company proposes to a group of individuals of varying knowledge, heterogeneity, and number, via a flexible open call, the voluntary undertaking of a task. The undertaking of the task, of variable complexity and modularity, and in which the crowd should participate bringing their work, money, knowledge and/or experience, always entails mutual benefit. The user will receive the satisfaction of a given type of need, be it economic, social recognition, self-esteem, or the development of individual skills, while the crowdsourcer will obtain and utilize to their advantage that what the user has brought to the venture, whose form will depend on the type of activity undertaken.

(Estellés and González-Ladrón, 2012:198)

The definition covers the three key elements of crowdsourcing activities: the crowd, the initiator and the process, with an emphasis on the benefits for both the crowd and the initiating organization: The crowd, the initiator and the process. The crowd refers to participants of crowdsourcing projects. They are not employees or workers along a company’s value chain; rather, they are a large group of ‘distributed, plural, collaborative’ individuals (Brabham, 2008). The so-called ‘crowd’ is usually regarded as non-experts or amateurs, but previous surveys showed that its composition often include people with professional credentials (Estellés and González-Ladrón, 2012). They can participate in crowdsourcing projects as an individual, but in many cases they collaborate with each other. Franke and Sonali (2003) for example observed that a lot of product innovation happens within voluntarily assembled communities of end-users. As contributors are not constrained by contractual obligations, they choose whether or not to offer their support at free will, driven either by intrinsic or extrinsic needs (Lakhani et al., 2007).

The initiator is an organization or an individual who puts up a task and asks for the crowd’s voluntary support. It can be for-profit or not-for-profit by nature, it is often assumed that the key benefit of using online voluntary resources is cost reduction, since contributors generally receive small or no financial rewards (Borst, 2010).

The process of crowdsourcing can be seen as a model of problem solving, production, open innovation, business strategy, customer engagement or labor management, depending on the underlying purpose of the organizing firm. Despite the difference in how each organization orchestrates such activities, the Internet is almost present in all crowdsourcing processes. As Malone et al. (2010) pointed out, wider accessibility of tools and communication technologies has enabled communities to connect and collaborate, creating a virtual world of collective intelligence.

Crowdsourced translation initiatives can be divided into three types: outsourcing-driven (projects initiated by for-profit companies in similar ways they would outsource the task), product-driven (localization of free software for common usage), and cause-driven (projects initiated by not-for-profit organizations for a cause) (McDonough, 2012). While outsourcing driven projects involve for-profit companies such as Facebook calling for users to localize its interface into different languages, usually to boost user engagement, product-driven initiatives allow translators to make computer programs or open-source software available to a broader user base.

But beyond outsourcing to a crowd on a voluntary basis, volunteering in general is not a new phenomenon. It has aroused academic fascination, as reflected in the numerous scientific studies focussing on the motivations of those who devote their time and effort to unpaid work. This will be explored further, after having provided a theoretical framework for the research questions about volunteer translators’ motivations.

This phenomenon has been seen as a professional intrusion and a threat to the translation profession; although instances of collaborative translation where professionals and non-professionals translators work together can be found historically in the translations of books, and communities of practice where member exchange knowledge are not uncommon among translators (Risku and Dickinson, 2009). Some professional translators formalized their complaint in a public petition for responsible public advocacy against crowdsourcing (Professional Translators Against Crowdsourcing and Other Unethical Business Practices). The leitmotiv is to highlight the quality of work delivered by professional, as opposed to non-professional, translators. However, some previous studies contradict such claims with scientific evidence (Zaidan and Callison-Burch, 2011).

But, beyond these disputes, echoing old quality-based arguments between Wikipedia and Britannica, one of which was published in the scientific journal Nature (Giles, 2005), many voices point to the benefits for the global community of having volunteer translators.

Volunteer translation removes language barriers and allows a global community to access all kinds of information, data and knowledge, which would otherwise be blocked by the impossibility of paying for translations. Eventually, all this translated material can be used to improve the performance of computer-assisted translation systems, machine translation systems, terminology extractors and cross-language information retrieval systems. In turn, such language technologies help address the above mentioned challenge.

2. Case Study: OTP

• Why do people spend so many hours of their time translating, without expecting money in return? What are their motivations for doing so?

• What are these people’s profiles?

To answer our research questions, first the scope of the study will be defined by focusing on the OTP. Within the TED community, many of the most interesting and innovative scientific projects are presented at academic conferences organized by TED, and made available for free on the Internet, including captions and timing information or audio and video files, all shared under a Creative Commons license.

TED derives its global characteristic not from the number of registered members (currently around 1.5 million), but from the diversity of these members and the number of Internet views: currently over one billion. As the OTP became more widespread and gathered more volunteers translating TEDTalks into 100 languages, the multilingual repository also grew in size.

TED launched its Open Translation Project in 2009 to make TED talks more accessible to linguistically and culturally diverse communities. Tapping the powerful idea of crowdsourcing, TED talks are now available in 100 languages, with more than 12,000 volunteer translators and more than 42,000 completed translations.

The OTP is about accessibility in that it removes the linguistic barriers to the spread of knowledge. In contrast to the dominance of English as the language of publication for almost all scientific talks, the OTP gives users around the globe the opportunity to subtitle the talks transcribed in English and published on the TED website into different languages. This project and also Wikipedia would fall under the cause-driven category, with clear mission statements to spread knowledge further.

To facilitate this process, the OTP provides an online tool, Amara2, for ‘interlingual subtitling’; a term that describes the technique of translating from a source language into a target language (or languages) in the form of one or more lines of synchronized written text. Using the Amara platform volunteers create multilingual content, making TED a social media platform, ‘social media’ being a term used to describe web services whose content is edited by their users on a voluntary basis (Lietsala and Sirkkunen, 2008). Other successful cases demonstrate the scope of social media; these include Wikipedia, online dictionaries that are updated by suggestions from users (Wordreference, LEO), Google Translator, where users can participate by suggesting better translations than those proposed by the system, (Cámara and Espasa, 2011) and Fan Subs, the predecessors of online subtitling projects (Pérez-González, 2006).

The TED OTP translation workflow consists of three stages: translation, review, and approval; translation and review tasks are in charge of regular volunteer translators; the approval stage is managed by language coordinators (LCs).3

3. Towards a definition of ‘Motivation’ and ‘Virtual Volunteering’

Before discussing volunteers’ motivations and a global volunteering trend of crowdsourcing through social media, it is useful to define the key terms constituting this framework: motivation and virtual volunteering.

The case study discussed in this paper relates to volunteers who perform their tasks online, and interact within a virtual community, which, with further explanations about volunteering and virtual community research, forms the basis of our theoretical framework. This guides the research, determining what will be measured, and what relationships will be examined.

3.1. Motivation

Motivation is the psychological attribute that drives a person to action. This simple concept has long been a central topic in the study of both animal and human psychology. Early humanistic psychologists focussing on motivation factors outlined a number of theories and models that aimed to classify the different kinds of motivations. One example is Maslow’s theory of human motivation (1943);

Fig.1: Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

The theory of human motivation was later extended by Alderfer and enshrined in the New Theory of Human Needs (1969). Alderfer based his theory on a 3-fold conceptualization of human needs: existence, relatedness, and growth.

While these theories rely on human need as a basis for identifying the reasons for our actions, new approaches separate motivations from human needs, as such.

Moreover, according to the literature consulted, people are driven to do something by two kinds of motivation: Intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation.

• Intrinsic motivation: people perform an activity because they find it interesting and derive spontaneous satisfaction from the activity itself (Gagné and Deci, 2005). Intrinsic motivation implies therefore that people are driven to do things because they matter, they like it, they’re interesting, because they are part of something important4.

• Extrinsic motivation: people perform an activity for the sake of receiving compensation or other rewards (Deci, 1971; Frey and Oberholzer-Gee, 1997). This does not mean, however, that a person will not get any pleasure from working on a task, or that extrinsic motivations operate at the exclusion of intrinsic motivations.

However varied, these definitions of ‘motivation’ all contain elements that are universally recognized as human features, and all are crucial to the approach taken in our paper.

The UN defines volunteering as something undertaken for which the volunteer receives no personal direct benefit, that is done of their own free will and that benefits another person or persons.

Thus, a volunteer is a person who voluntarily offers himself or herself to the solidarity action without being paid for it within an organization.

And a TED volunteer translator could be defined as follows:

a person who voluntarily translates or reviews, without being paid for his/her time or expertise, the subtitles of academic conferences approaching socio-political, cultural, and educational research fields within a private non-profit foundation —The Sapling Foundation.

Notwithstanding the foregoing definition, the fact that TED translators perform their tasks online and interact in a virtual community requires close attention. The next subsection is dedicated to explaining this social change, which has been receiving increasing academic attention.

3.2. Virtual Volunteering

According to Cravens (2000), ‘online volunteering’ also known as ‘virtual volunteering’ means volunteer activities that are completed, in whole or in part, via the Internet on a home, work, or public access computer, usually in support of or through a mission-based organization (non-profit, NGO, civil society, etc.).

Virtual Volunteering opens up new possibilities for individuals to contribute their expertise and time direct from home or the office, without leaving their comfort zone, as defined by White (2009):

The comfort zone is a behavioural state within which a person operates in an anxiety-neutral condition, using a limited set of behaviours to deliver a steady level of performance, usually without a sense of risk.

Online volunteering has grown over more than 30 years along with the expanding Internet and the increase in popularity of online social networks to national and global levels. Project Gutenberg5 is one of the oldest examples of digital volunteering.

Other more recent initiatives such as the Online Volunteering Service of the United Nations Volunteers has received over 26,000 applications since 2001 and attracted 13,000 volunteers from 182 countries6.

Online volunteering activities include: translation, research, website design, data analysis, database construction, online discussion facilitation or moderation, proposal writing, production of articles, mentoring, coaching, tutoring, professional advice, curriculum development, publication design, and more.

If such activities are supported by a mission-based organization, as defined by Craven, volunteers may build up a virtual community. Following this definition, the OTP constitutes an online volunteering project that involves not only a virtual community with its own features, but a social network aside from the huge TED Community. Founded on shared ideas and values, the OTP can be seen as a tribe, following Godin (2007), who described an Internet-based tribe as the revival of a human social unit from the distant past, giving ordinary people the power to lead and make big changes.

Even if the distributed nature of online volunteers enabled organizations, in this case TED, in order to mobilize people from all over the world with their cultural differences, those volunteers establish cultural bridges around a mission, being also cultural mediators.

3.3. 3.3. Volunteers’ motivation

Our analysis uses the Volunteer Motivation Inventory (VMI) as a reference. After Esmond and Dunlop reformulated this inventory in 2004, it has been seen as a standardization of previous VMIs.

This new version pays tribute to the outstanding results obtained by Clary, Snyder and Ridge (1992), who fully revised the classical theories of research settings. They conducted an explicitly empirical investigation of volunteer work and motivations from a functional perspective. Widely acknowledged in specialized literature, their work arrives at six key factors underpinning the spectrum of motivations that drive volunteers to work for free: values, understanding, career, social factors, esteem and protection.

Esmond and Dunlop increased these six motivating factors to ten: values, reciprocity, recognition, understanding, self-esteem, reactivity, social, protection, social interaction and career development.

In the OTP Motivation Inventory Ranking section below, it be discussed the points at which the VMI and our user research results intersect.

4. Methodology: Data Collection Instrument and Procedures

4.1. Background

After explaining the purpose of the study and determining the objectives described above, I then tried to find other empirical surveys focussing on volunteer motivations in the translation environment. This review revealed little in terms of empirical research. Instead, I found a significant preliminary interview-based study that asked a number of translators the question ‘Why do I translate TEDTalks?’.

Before describing the data collection procedures further, the following section develops the choice of tool used to collect data.

4.2. Interview, and Questionnaire

The sample consisted of 177 questionnaires. The data gathering was carried out between June 25th, 2012 and September 6th, 2013.

4.2.1. Data-gathering method

In order to survey a large number of respondents I generated a self-administered structured questionnaire consisting of closed questions of nominal categorical type. For the purpose of this study, a survey of this type is more suitable because it is less time consuming, relatively easy to compare multiple alternatives, results can be automatically tallied, it protects respondents’ anonymity, and since questionnaires are online, this type of survey has a global reach.

4.2.2. Structure of the questionnaire

The questionnaire was divided into two parts: closed-ended questions and a multiple choice motivation catalogue.

The first part was designed to outline a tentative user profile, and it focused on individuals with a background in bilingualism, in some cases even multilingualism, cross-cultural communication and translation education:

• Demography: age, sex, country and city of birth, country and city of residence.

• Ethno-linguistic identification and background: official language(s) of the country and city of birth, official language(s) of the country and city of residence, home language(s), language of instruction or language used at school.

• Professional occupation: economic activity status, occupation.

• Education in translation, and specifically in audiovisual translation (subtitling).

The second part is a clickable list of multiple choice, stemming from semi-structured personal interviews with language coordinators (LCs). The final OTP Volunteer Translator Motivation Inventory resulting from this research consisted of 21 short statements, to which volunteers would respond by choosing all those applicable to them. The result of the Inventory is listed and ranked according to participants’ answers in the OTP Motivation Inventory Ranking section below.

4.2.3. Questionnaire Dissemination

In order to obtain voluntary responses, the questionnaire was posted online and invitations to complete it were distributed through the I translate TEDTalks site, and the TED LCs Facebook communities.

5. Results

5.1. Socio-demographic Variables: Gender, Age and Profession

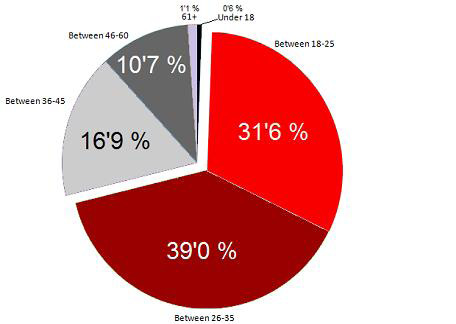

Fig. 2: Age Groups Distribution

In this study the age spectrum of the respondents ranged from 18–65 years old. The statistical distribution resembles a Gaussian curve, with the bulk of respondents sitting between the 18-35 age group and with moderate values at the beginning and end of the overall distribution.

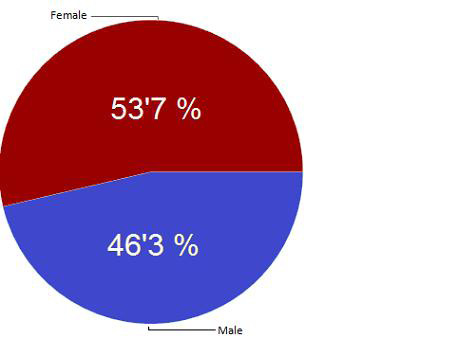

Fig. 3: Gender Distribution

The percentages of male and female volunteers are similar, 54% female and 46% male, and crossing the gender data by age group, I found no clear trend in gender differences. This result suggests that the distribution of male to female volunteers is 50-50, except for the 36-45 group, where women account for 66%.

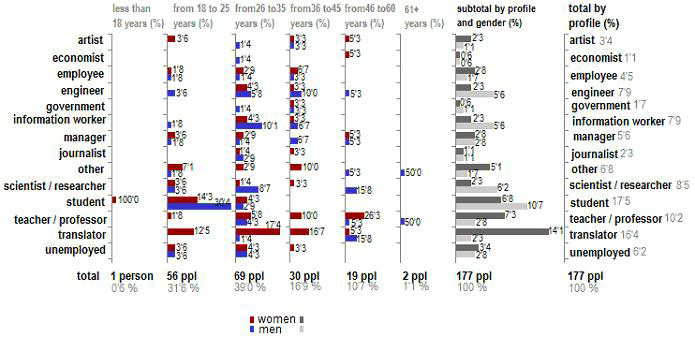

The following graph shows the professional user profiles by gender and age group.

Fig. 4: User profile by profession, gender and age group

The participants’ profile in the 18-35 group is dominated by the following professions: 17.5% students, 16.4% translators, 10.2% teachers, 8.5% scientists or researchers, 8% engineers, 8% information workers. The remaining percentage is made up of managers, employees, artists, journalists, economists, consultants, etc.; 6.2% are unemployed. In particular, the 18-25 group, which accounts for 31.6% of the total, is constituted by a significant number of male students. In contrast, the 26-35 group, which accounts for 39% of the total, shows a clear preponderance (66%) of women, 17% of whom are translators.

The remaining age groups show an equitable representation of men and women. This finding is supported by the hypothesis that Johanna Blakley (2010) raised in her academic talk on Social media and the end of gender:

When you look online at the way people aggregate, they don’t aggregate around age, gender and income. They aggregate around the things they love, the things that they like. And if you think about it, shared interests and values are far more powerful aggregator of human beings than demographic categories. I’d much rather know whether you like ‘Buffy the Vampire Slayer’ rather than how old you are. That would tell me something more substantial about you.

5.2. Translation Training and Education

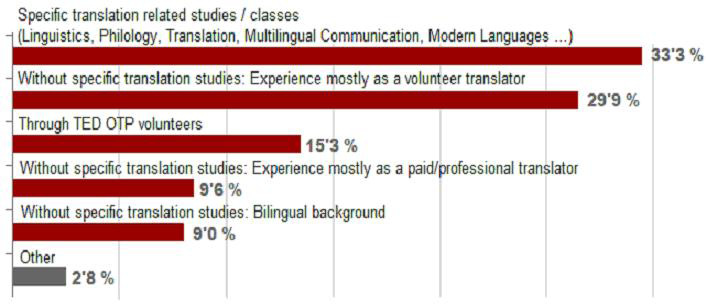

Analysing the variables related to education and translation training —shown below in Fig. 5 — 33% of the respondents have some formal education in translation. The remaining respondents said they didn’t have any specific formal education. Instead, these respondents had experience in volunteer translation (30%), or specifically, in volunteer translation for the OTP (15.5%).

Fig. 5: Training on translation

Another 9.6% of those without a specific formal background in translation have gained experience by translating on demand and been paid for these services. And finally, there is another 9% without a formal background in translations who belong to a bilingual environment which prepared them to engage in translation activities.

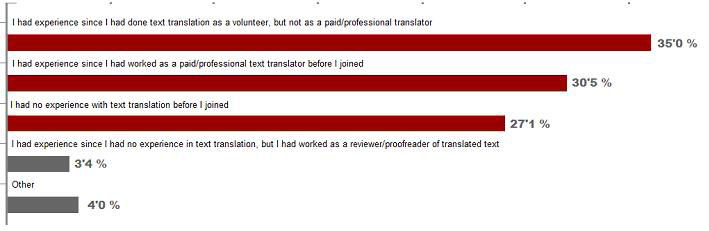

Taking into account the above mentioned characteristics, about 70% of the respondents claim to have direct or indirect translation backgrounds: 35% of them had gained text translation experience as volunteers, but not as paid/professional translators; another 30.5% had experience as paid/professional text translators before joining OTP; and the remaining 3.4% had worked as reviewers/proof-readers of translated texts.

Fig. 6: Experience in translating texts as opposed to translating subtitles before joining OTP

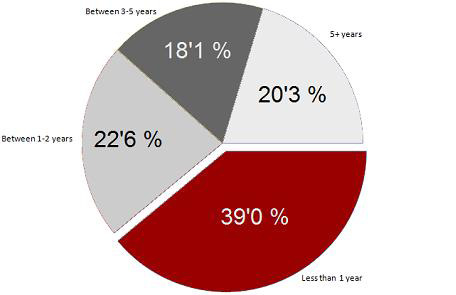

Fig. 7: Distribution of years of experience in text translation

Considering the number of years of experience gained in text translation before joining the OTP, 39% of the respondents had less than 1 year; 22.6% had between 1-2 years; 18.1% had between 3-5 years and 20.3% had over 5 years of experience in the field.

The figures for non training and experience in audiovisual translation are significant, especially subtitling and translating subtitles.

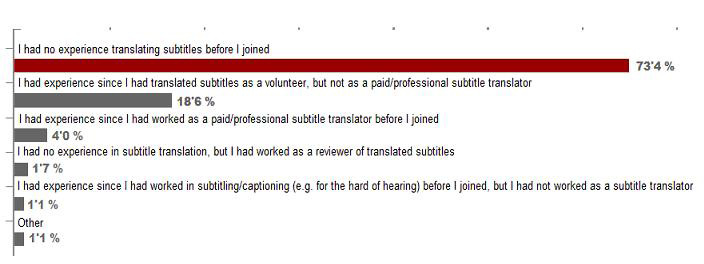

Fig. 8: Experience in translating subtitles as opposed to different types of text before joining OTP

73% of the respondents reported they had no training in subtitling before joining the OTP, while 26% said they had previous audiovisual translation backgrounds before joining the OTP.

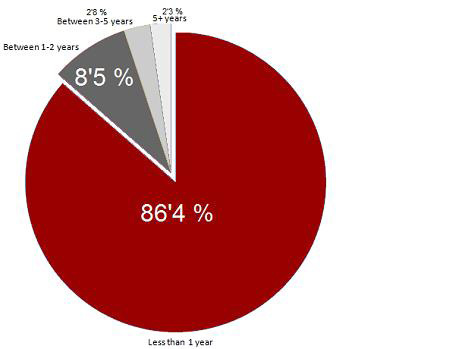

Of the great majority of those with a previous background in audiovisual translation, 86.4% had less than one year of experience.

8.5% had between 1-2 years of experience in subtitling before joining the OTP; 2.8% had between 3-5 and 2.3% had more than 5 years.

Fig. 9: Distribution of years of experience in subtitle translation.

Also, as I shall see below (Fig. 11), two of the five most commonly selected motivations in the TED Specific Motivations Inventory are related to the possibility of learning through subtitling:

• I wish to gain more experience and skills translating.

• Translating the subtitles allows me to learn more about the talks that I translate.

Therefore, it can be concluded that this project helps its members learn more efficiently and to use the translation of subtitles as a learning strategy to acquire plurilinguistic skills.

These results coincide with the widely-made claim that students attending subtitling courses improve their linguistic skills in the first and second language, and that this activity contributes towards the consolidation of content (Klerkx, 1998; Williams and Thorne, 2000; Rundle, 2000; Neves, 2004; Sokoli, et al., 2011). The reasons given are inherent to the act of subtitling. This task yields a hands-on result, which can motivate and facilitate learning, providing an ideal environment for the development of receptive and productive linguistic skills: listening, reading, comprehension, and writing (reducing, paraphrasing).

5.3. Intercultural competence background

In a previous section, socio-demographic variables of age, gender and profession were analysed. I have also dedicated a section to analysing experience gained in textual translation and subtitles, without explaining why I have used these indicators to set a profile of OTP volunteers. Therefore, by addressing the concept of intercultural competence background I can at this point clarify two things. First, it is useful to define this concept and, second, it is important to explain why I selected specific intercultural indicators in our articulation of a common denominator shared by such a diverse group.

The United States Army Research Institute has defined intercultural competence as ‘a set of cognitive, behavioural, and affective/motivational components that enable individuals to adapt effectively in intercultural environments.’ (Abbe, 2007)

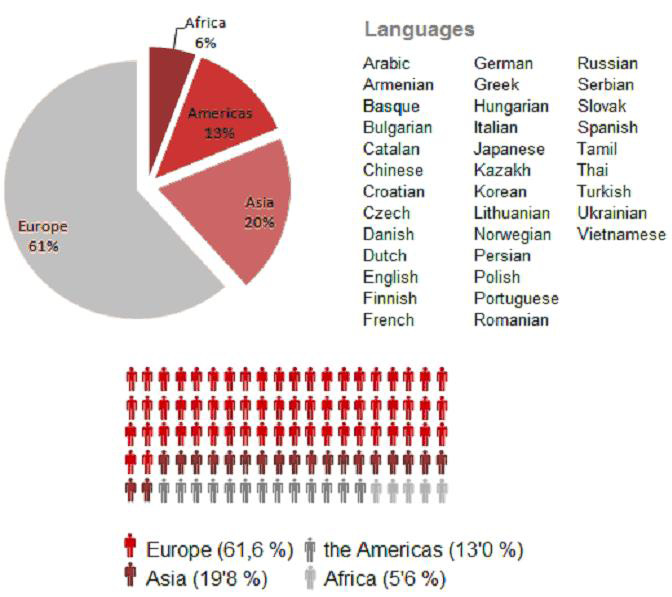

Intercultural competence can also be defined as a complex of abilities needed to perform effectively and appropriately when interacting with others who are linguistically and culturally different from oneself (Fantini, 2006:12). The foundation for these abilities is emotional competence (empathy), together with intercultural sensitivity (openness to the new, to difference). Fantini also details a range of more or less related terms that describe intercultural competence, such as intercultural communicative competence, transcultural communication, cross-cultural adaptation, intercultural sensitivity, among others. The fine-grained differences between these research terms is beyond the scope of this paper. Notwithstanding, as shown in Fig. 10, I have addressed this complex issue by asking a group of 177 participants, geographically distributed over four continents, who collectively represent up to 35 language groups, to pinpoint the key motivation factors for becoming volunteer translators.

Fig. 10: Native Language of Participants (above)-Distribution by Participants’ continent of origin (below)

According to the INCA (2004) framework for intercultural competence, certain factors influence how I respond to intercultural situations, namely:

• Family background

• Time spent living abroad (long term stay)

• Work experience in other countries

• Time spent in a multicultural community in home country

• Travel to other countries (short term visits) for holiday or work purposes

• Social contacts, friends from abroad

• Social contacts, friends from within multicultural community in home country

Our survey specifically addressed the first two items listed above through questions about:

• Country of birth and city of birth

• Home language(s), language(s) spoken at home

• Official language(s) of the country and city of birth

• Country of residence and city of residence

• Language of instruction or language used at school (not to be confused with the foreign language learnt at school)

• Official language(s) of the country and city of residence

The results obtained are detailed below.

33.9% of the respondents were born in a city culturally and linguistically different from their place of residence, while 61.1% live in their city of birth or in another city in the same country and communicate in the language of their home city.

44.6% of the respondents speak or spoke at home a language other than the school language or language of instruction; 39% with training in translation have an intercultural background; 40.7% without training in translation have an intercultural background.

The very nature of OTP and how volunteers from around the world interact implies that the members develop their intercultural competence through the social contact that they have with members from all over the world.

From a linguistic perspective, there is evidence that under certain circumstances, living with two or more languages can bring advantages, not only in linguistic knowledge but also in terms of cognitive and socio-pragmatic development. I count the following among these advantages: a heightened level of meta-linguistic awareness, creative or divergent thinking such as flexibility and originality regarding conventional thinking (Cummins, 1977; Srivastava, 1991), communicative sensitivity, for example, greater sensitivity to sociolinguistic interactions with interlocutors (Goetz, 2003) or more sensitivity to interpersonal communication (Genesee, Tucker and Lambert, 1975) and further language learning (e.g. Mohanty 1994; Baker 2006).

Therefore, translating the ideas of persons with different languages, nationalities, religions and cultures is by nature a task that fosters intercultural competences, by linguistically and culturally crossing diverse borders. This entails adding new language-culture systems to the native language and cultural system and extending one’s own culture with an open respectful attitude. According to Ibañez and López-Sáenz (2006), interculturalism involves moving beyond mere passive acceptance of a multicultural fact of multiple cultures effectively existing in a society and instead promotes dialogue and interaction between cultures.

The most illuminating example of this is Dafa-Alla (2012), one of the Arabic LC at the OTP. He comes from and lives in the Sudan; he has lived for several years in South Korea, while working on his PhD. In his speech ‘Crossing your inner borders’ in Berlin, he illustrates an attitude which clearly expresses the link between translating other people’s ideas and the challenge of opening ourselves to developing empathy towards others, escaping from ideas that are anchored in the past, rooted in explicit context, and driven by specific traditions.

5.4. OTP Motivation Inventory Ranking

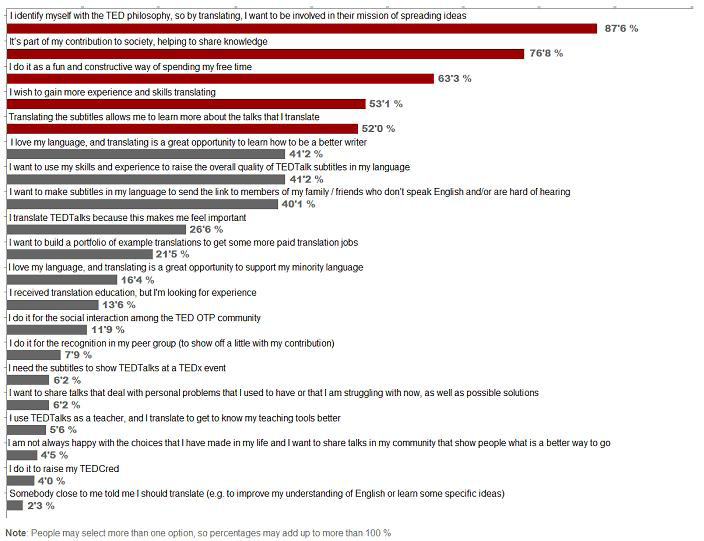

The following figure shows the resulting twenty-one motivational factors, which are ranked according to participants’ responses.

Fig. 11: OTP Volunteers’ Motivation

The highest ranked motivations are intrinsically related to values, reciprocity, enjoying free time and learning.

1. Values (87.6%): I identify myself with the TED philosophy, so by translating, I want to be involved in their mission of spreading ideas. McDonough’s survey on volunteer translators of Wikipedia (2012) revealed also that making information accessible to other language users and helping the organization they volunteer for are the top reasons for volunteering.

2. Reciprocity (76.8%): It’s part of my contribution to society, helping to share knowledge.

3. Enjoying Free Time (63.3%): I do it as a fun and constructive way of spending my free time. ‘If you want to understand the global village, it’s probably a good idea that you figure out what they are passionate about, what amuses them, what they choose to do in their free time.’ Blakley’s words illustrate the third driving force among OTP volunteers.

4. and 5. Learning: I wish to gain more experience and skills translating (53.1%); translating the subtitles allows me to learn more about the talks that I translate (52.0%). As many volunteers are regular viewers of TED Talks, they are willing to devote their time translating talks going deeper to the content of a talk, similar to studies of other crowdsourcing projects (e.g. Lakhani and Wolf, 2007). The OTP has also attracted a fair amount of professional and non-professional translators to participate who either enjoy translation activity or use it as an opportunity to enhance their skills.

6. Discussion and conclusion

Our user research results agree with the findings of authors such as Blakley (2010), Esmond and Dunlop (2004), and Clary, Snyder and Ridge (1992) on three motivators driving OTP members: values, reciprocity and enjoying free time. In addition, the potential for learning is a crucial motivational factor that could also be understood as understanding, if I aim to match the motivational factor listed in the above-cited studies.

In conclusion, TED volunteer translators are driven by

• Playing an active and interactive role in the expansion of the TED mission

• Making the most of their free time while enjoying themselves

• Having a platform to acquire subtitling skills, and experience inter-cultural interaction through informal learning processes

Overall, their profiles are quite diverse, nevertheless, I can identify some general patterns.

The bulk of the respondents are aged between 18-35 years old and noticeably in the 18-25 segment, many are male students. In the 36-45 segment, representing 17% of the total, most of the respondents –66%– are female translators. In the other age segments, the ratio of male to female respondents is balanced.

A large number of professionals are working as translators, teachers, scientists, researchers, and engineers or working within the information sciences (journalism, audiovisual communication, etc).

The great majority have some kind of academic qualification. One out of three has professional translation skills. A noteworthy fact found is that 3/4 of the respondents had no qualification in subtitling before joining the OTP. And out of the ¼ having previous experience in subtitling, 86% have less than one year of experience in the field. Thus, the OTP acted as a platform for acquiring new subtitling skills.

Almost half of the respondents – 40% – exhibit an intercultural and transcultural background in translation even though the overall educational background is rather diverse. Correspondingly, 34% of the respondents were born in a multicultural environment, and 45% spoke a different language at home from the language of instruction.

In this sense, it can be reasonably affirmed that by addressing intercultural competence from a modern social psychology perspective and from a linguistic-translation perspective, OTP participants can be seen as the champions of interculturalism. They share and help to share dialogue and knowledge across cultures by means of language, as an asset contributing to build cultural bridges which ultimately let them also develop their understanding of translation issues from varied perspectives –considering that they are interacting with a community of people speaking over 100 other languages, very often representing a myriad of different idiosyncratic perspectives on the same issues– contributing to an understanding of the complexity of communicating across cultures, nations, and linguistic borders.

Furthermore, by promoting informal learning in audiovisual translation with the mission of spreading ideas across the world, OTP supports intercultural competences, wherein translation is considered a form of mediation between cultures, and the contents of the translated talks deal with multiple issues, perspectives, and cultural backgrounds.

This competence is just one among other mandatory competences which prove professionalism in translation. In this vein, the quality criteria which are applied by volunteers in environments such as the TED OTP remains an open question needing analysis. This might be worth exploring, especially if formal learning environments for acquiring translations skills want to benefit from those increasing motivating social activities.

7. References

• Abbe, A., Gulick, L.M.V., and Herman, J.L. (2007). ‘Cross-cultural competence in Army leaders: A conceptual and empirical foundation’. Washington, DC: U.S. Army Research Institute.

• Alderfer, C. (1969). Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 4 (2), 142-175.

• Baker, C. (2006). Foundations of Bilingualism and Bilingual Education, Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

• Blakley, J. (2010). ‘Social media and the end of gender’. TED Conferences. [Video recorded Dec.2010] [online] http://www.ted.com/talks/lang/en/johanna_blakley_social_media_and_the_end_of_gender.html (Accessed 05 January 2014).

• Brabham, D.C. (2008). ‘Crowdsourcing as a model for problem solving: An introduction and cases’. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 14(1), 75-90.

• Borst, W.A.M. (2010). Understanding Crowdsourcing: Effects of motivation and rewards on participation and performance in voluntary online activities. (Doctoral dissertation, Erasmus Research Institute of Management, Erasmus University).

• Cámara, L. and Espasa. E. (2011). ‘The Audio Description of Scientific Multimedia’ Science and Translation. The Translator, 17 (2), 415-37, St Jerome Publishing.

• Clary, E. G., Snyder, M., and Ridge, R. (1992). ‘Volunteers motivations: A functional strategy for the recruitment, placement, and retention of volunteers’. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 2, 333-350.

• Cummins, J. (1977). ‘Cognitive factors associated with the attainment of intermediate levels of bilingual skills’, Modern Language Journal, 61, 3-12.

• Cravens, J. (2006). ‘Involving International Online Volunteers: Factors for Success, Organizational Benefits, and New Views of Community’. International Journal of Volunteer Administration, 24, 15-23. [online] http://www.ijova.org/PDF/VOL24_NO1/IJOVA_VOL24_NO1_Intl_Online_Vols_Jayne_Cravens.pdf (Accessed 05 January 2014).

• Dafa-Alla, A. (2012) ‘Crossing Your Inner Borders’ TEDx Berlin Conference. [Video recorded Oct. 2012.] [online] http://www.tedxberlin.de/tedxberlin-2012-crossing-borders-anwar-dafa-alla-crossing-your-inner-borders (Accessed 05 January 2014).

• Deci, E. L. (1971). ‘Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation’. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 18, 105-115.

• Esmond, J. and Dunlop, P. (2004). ‘Developing the Volunteer Motivation Inventory to Assess the Underlying Motivational Drives of Volunteers in Western Australia’. Perth: CLAN WA LotteryWest. [online] http://www.morevolunteers.com/resources/MotivationFinalReport.pdf (Accessed 05 January 2014).

• Estellés Arolas, E. and González Ladrón de Guevara, F. (2012). ‘Towards an integrated crowdsourcing definition’. Journal of Information Science, 38 (2), 189-200.

• Fantini, A. E. (2006). ‘Exploring and assessing intercultural competence’. Brattleboro, VT: Federation of the Experiment in International Living. [online] http://csd.wustl.edu/Publications/Documents/RP07-01.pdf (Accessed 05 January 2014).

• Franke, N. and Sonali, S. (2003). How communities support innovative activities: an exploration of assistance and sharing among end-users. Research Policy, 32 (1), 157-178.

• Frey, B. and Oberholzer-Gee, F. (1997). ‘The Cost of Price Incentives: An Empirical Analysis of Motivation Crowding-Out’, American Economic Review, American Economic Association, 87 (4), 746-55.

• Gagné, M. and Deci, L. (2005). ‘Self-determination theory and work motivation’. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26, 331-362.

• Giles, J. (2005). ‘Internet encyclopedias go head to head’, Nature, 438 (7070), 900.

• Genesee, F., Tucker G., and Lambert, W. (1975). ‘Communication skills of bilingual children’, Child Development, 46 (4), 1010-1014.

• Godin, S. (2009). ‘The tribes we lead.’ TED Conferences. [Video recorded Febr. 2009] [online] http://www.ted.com/talks/seth_godin_on_the_tribes_we_lead.html (Accessed 05 January 2014).

• Goetz, P. (2003). ‘The effects of bilingualism on theory of mind development’, Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 6, (1), 1-15.

• Ibañez, B. and López-Sáenz, Mª C. (2006). Interculturalism: Between Identity and Diversity. Bern: Peter Lang AG, 15.

• INCA. (2004). Portfolio Interkultureller Kompetenz. Leonardo-da-Vinci-II-Projekt 2001-2004 [online] http://www.incaproject.org/de_downloads/22_INCA_portfolio_German_final.pdf (Accessed 05 January 2014).

• Klerkx, J. (1998). ‘The place of subtitling in a translator training course’. In Gambier, Y. (Ed.) Translating for the Media. Turku: University of Turku, 259-264.

• Lakhani, K.R. and Wolf, R.G. (2003). ‘Why Hackers Do What They Do: Understanding Motivation and Effort in Free/ Open Source Software Projects’. In J. Feller, B. Fitzgerald, S.A. Hissam and K.R. Lakhani (Eds.) Perspectives on Free and Open Source Software. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

• Lietsala, K. and Sirkkunen, E. (2008). Social Media. Introduction to the Tools and Processes of Participatory Economy, Tampere: Tampere University Press.

• Malone, W.T., Laubacher R. and Dellarocas, C. (2010). ‘The Collective Intelligence Genome’, MIT Sloan Management Review 51 (3), 21-31.

• McDonough, D.J. (2012). ‘Analyzing the Crodsourcing Model and Its Impact on Public Perceptions of Translation’. The Translator, 18(2), 167-191.

• Maslow, A. H. (1943). ‘A Theory of Human Motivation’. In Classics in the History of Psychology, Christopher D. Green, York University, Toronto, [online] http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Maslow/motivation.htm (Accessed 05 January 2014).

• Messner, W and Schäfer, N. (2012). ‘Advancing Competencies for Global Collaboration’. In Bäumer, U., Kreutter, P., Messner, W. (Eds.) Globalization of Professional Services. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

• Mohanty, A. (1994). Bilingualism in a Multilingual Society: Psychosocial and Pedagogical Implications. Mysore: Central Institute of Indian Languages.

• Neves, J. (2004). ‘Language awareness through training in subtitling’. In Orero, P. (Ed.) Topics in Audiovisual Translation. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 127-140.

• O’Hagan, M. (2011). ‘Community translation: Translation as a social activity and its possible consequences in the advent of Web 2.0 and beyond’. Linguistica Antverpiensia, 10, 110.

• Pérez-González, L. (2006). ‘Fansubbing Anime: Insights into the Butterfly Effect of Globalisation on Audiovisual Translation’, Perspectives: Studies in Translatology, 14(4), 260-77.

• Risku, H. and Dickinson, A. (2009). ‘Translators as Networkers: The Role of Virtual 76 Communities’, Hermes, 42, 49-70.

• Rundle, C. (2000). ‘Using subtitles to teach translation’. Bollettieri, R.M./ Heiss, C./ Soffritti, M.: Quale traduzio ne per quale testo? Bologna: CLUEB, pp. 167-181.

• Sokoli, S., Zabalbeascoa P., Fountana M. (2011). ‘Subtitling Activities for Foreign Language Learning: What Learners and Teachers Think’. In Laura McLoughlin, Marie Biscio and Máire Áine Ní Mhainnín, (Eds.) Audiovisual translation Subtitles and Subtitling. Theory and Practice. Peter Lang.

• Srivastava, S. (1991). ‘Creativity and linguistic proficiency’. Psycho-Lingua, 21(2), 105-109.

• White, A. K. (2009). From Comfort Zone to Performance Management. White and MacLean Publishing.

• Williams, H. and Thorne, D. (2000). ‘The value of teletext subtitling as a medium for language learning’. System, 28 (2), 217-228.

• Zaidan, O. and Callison-Burch, C. (2011). ‘Crowdsourcing Translation: Professional Quality from Non-Professionals’. In ACL, Proceedings of the 49th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Portland [online] http://www.aclweb.org/anthology/, (Accessed 05 January 2014).

Notas