A Previously Unpublished Letter of Introduction by an Andalusi Karaite (T-S 8J41.7)*

Una carta de presentación inédita de un caraíta andalusí en la Guenizá de El Cairo (T-S 8J41.7)

José Martínez Delgado | Amir Ashur

pdelgado@ugr.es | amirash@tauex.tau.ac.il

Universidad de Granada | Tel Aviv University

ORCID ID: 0000-0001-7595-3912 | 0000-0002-9999-6535

Recibido: 10-9-2021 | Aceptado: 11-10-2021

https://doi.org/10.30827/meahhebreo.v70.22581

Abstract:

The document published in this article is a letter of introduction written by a Karaite Andalusi Jew upon his arrival to Egypt, on his route to Jerusalem. The text, which was deposited in the Cairo Genizah, is currently held at Cambridge University Library in the Taylor-Schechter Collection (Genizah Research Unit). Although undated, the text has the distinction of being the only known letter written by an Andalusi who presents himself as a Karaite, and is thus a first-person confirmation of the presence of this religious group in al-Andalus.

Keywords: Cairo Geniza; Karaites; Andalus; Alexandria

Resumen:

El documento que nos ocupa es una carta de presentación escrita por un judío andalusí caraíta al llegar a Egipto en su camino a Jerusalén. El texto, que fue depositado en la Guenizá de El Cairo, se encuentra actualmente en la Biblioteca de la Universidad de Cambridge en la Colección Taylor-Schechter (Genizah Research Unit). Aunque no está fechado, el texto tiene la particularidad de ser la única carta conocida escrita por un andalusí que se presenta a sí mismo como caraíta, por lo que es una confirmación en primera persona de la presencia de este grupo religioso en al-Andalus.

Palabras clave: Guenizá de El Cairo; Caraítas; al-Andalus; Alejandría

*This work was done under the auspices of the research project, Legado Judeo-Árabe de al-Andalus: Patrimonio Lingüístico (Reference PGC2018-094407-B-I00), funded by the ERDF / Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades – Agencia Estatal de Investigación. We wish to thank Prof. M.A Friedman, Dr. Rachel Hasson and Alan Elbaum for their comments.

cómo citar este trabajo | how to cite this paper

Martínez Delgado, J., & Ashur, A. (2021), A Previously Unpublished Letter of Introduction by an Andalusi Karaite (T-S 8J41.7). Miscelánea de Estudios Árabes y Hebraicos. Sección Hebreo, 70, 193-207. https://doi.org/10.30827/meahhebreo.v70.22581

Because of the dispersion of the people who practice Judaism, this religion has never been – nor can ever be – uniform. Indeed, as far back as the Middle Ages, it is possible to find a number of religious groups and schisms, most of which formed around the ancient rabbis, followed in importance by the Karaites of the East and the Samaritans of Palestine. Karaism 1, the schism that is the subject of this report, is a religious movement whose origin is both murky and disputed. Tradition holds that it was founded by Anan ben David (c. 715-c. 795), a member of a noble Jewish family that descended from King David. Resentful after being passed over for the position of exilarch, Anan then proclaimed the right of every Jew to study the Hebrew Bible freely, dismissing the interpretations of the rabbis and their Talmud. The followers of this movement are known as Ananites for their founder or Karaites for their adherence and attachment to the Bible (Mikra in Hebrew). At this time, it is not entirely clear whether this was originally a single group, given that both are rooted in the same idea that the Oral Torah is not the divine word.

After it appeared, Karaism spread like wildfire around Palestine, Syria and Egypt, reaching as far as al-Andalus. In Jerusalem, a splendid Karaite community flourished between the ninth and eleventh centuries, until the city was destroyed during the Crusades 2. According to tradition, many of them had settled in Khazaria, where the king converted to Judaism in the late eighth century. The story roused the interest and curiosity of Andalusi Jews during the first years of the caliphate, when this kingdom no longer existed 3, and centuries later, Khazaria would inspire the poet Judah ha-Levi to write his apologetics work, Kitāb al-radd wa-l-dalīl fī l-dīn al-dhalīl ‘The Book of Refutation and Proof on the Despised Faith’, popularly known as al-Khazarī in Arabic and ha-kuzari in Hebrew (in both cases, ‘The Khazar’), in reference to King Joseph of the mythical kingdom 4. Karaism spread rapidly throughout the Islamic world, producing an intellectual reaction in the rabbinate circles.

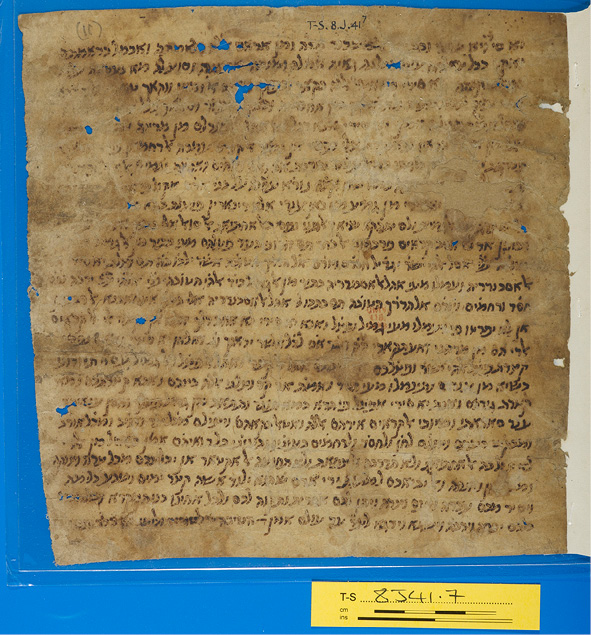

The document examined in this article is a letter of introduction written by a Karaite Andalusi Jew upon his arrival to Alexandria, on his route to Jerusalem 5. The text, which was deposited in the Cairo Genizah, is currently held at Cambridge University Library in the Taylor-Schechter Collection (Genizah Research Unit), under the shelf mark T-S 8j41.7. Although undated, the text has the distinction of being the only known letter written by an Andalusi who presents himself as a Karaite, and is thus a first-person confirmation of the presence of this religious group in al-Andalus. While scholars were aware of this fact, the evidence from Andalusi sources – both Islamic and Jewish – was hitherto indirect.

The Islamic sources are the oldest. One such case is the renowned Andalusi theologian ʿAlī ibn Hazm (Cordoba 994-Niebla 1064), who dedicated a specific chapter in his work, al-Fiṣal fī l-milal wa-l-ahwaʾ wa-l-nihal ‘Judgement regarding Religions, Inclinations ans Sects’, to the dhimmis, or ahl al-kitāb, entitled al-kalām ʿalā al-yahūd wa-ʿalā man ankar al-tathlīth min al-naṣārā wa-madhhab al-ṣābaʾīn wa-ʿalā man aqarr bi-nubuwwat Zarādusht min al-majūs wa-ankar min sawāhi min anbiyāʾ ʿalayhim al-salām ‘Discourse on the Jews, and on those Christians who deny the Trinity, the school of the Sabaeans and on those of the Zoroastrians (majūs) who recognize the prophecy of the Zoroaster, but deny the rest of prophets, peace be upon them’. This chapter includes the first allusion to the presence of Karaite Jews in al-Andalus by an Andalusi Muslim 6:

Abū Muḥammad (ʿAlī b. Hazm), may God have mercy upon him, said: the people of this religion, I mean the Jews, and the people of this sect, I mean the anti-Trinitarian Christians, agree with us (the Muslims) in our belief in monotheism, in prophecy, in the signs of the prophets, may peace be upon them, and in the revelation of the books by God, strong and lofty; they differ from us in (believing in) some prophets, may peace be upon them, and (denying) others. Similarly, the Sabaeans and Magians agree with us in believing in some prophets and (denying) others.

For their part, the Jews have divided into five groups (firaq):

- The Samaritans (al-sāmiriyya): they maintain that the holy city is Nablus, some eighteen miles from Jerusalem, they do not recognize or venerate the sanctity of the Temple of Jerusalem, they use a Torah that is different from that of the other Jews and they deny all prophecy of the Israelites after Moses, may peace be upon him, and Joshua, may peace be upon him, rejecting the prophecies of Samuel, 7 David, Solomon, Isaiah, Elisha, Elijah, Amos, Habakkuk, Zechariah, Jeremiah and the rest; they do not believe in any of the forms of the resurrection. They live in the Levant and they do not deem it permissible to leave there.

- The Zadokites (al-ṣadūqiyya): they are connected to a man named Zadok, they maintain, unlike the other Jews, that Ezra 8 is the son of God, God forbid. They are in the region of Yemen.

- The Ananites (al-ʿanāniyya): they are the followers of Anan, descendant of David of the tribe of Judah and they are called Karaite Jews (al-qarāyīn [< al-qarāʾiyyīn]) and it is a lie 9. They do not transgress the laws of the Torah or the prophets, peace be upon them, but they consider themselves exempt from the sayings of the sages (rabbis) and renounce them. This group is in Iraq, Egypt and the Levant. They are in al-Andalus, Toledo and in Talavera.

- The rabbis (al-rabāniyya): they are the ušʿaniyya 10. They adhere to the sayings of the sages and their doctrines. They make up the majority of the Jews.

- The Isawiyas (al-ʿisawiyya): these are the followers of Abī ʿĪsā of Isfahan, a Jew from Isfahan who I have heard was called Muhammad ben ʿĪsā. They profess the prophecy of Jesus (ʿĪsā), son of Mary, and of Muhammad, may God bless and keep him. They maintain that Jesus was sent by God, strong and venerable, to the Israelites to bring the Gospel to them and that he is one of the prophets of Israel. They maintain that Muhammad, may God bless and keep him, is a prophet sent by God on high with the laws of the Qur’an to the descendants of Ishmael, may God bless him, and the other Arabs, just as Job prophesized for the descendants of Esau and Balaam prophesized for the descendants of Moab, according to the beliefs of all the Jewish groups.

The Jewish sources, on the other hand, date back to the Almohad period (12th c.), specifically the work by the Cordovan Abraham ibn Daud (c. 1110-1180), Sefer ha-qabbalah or ‘The Book of the Tradition’. Early on, he mentions the presence of Karaite descendants in Toledo who follow the doctrine of the rabbis, 11 but he later recounts the following anecdote, which took place beyond the borders of al-Andalus, in the domain of Alfonso VII of Leon (r. 1126-1157), which includes a criticism of a woman known as al-Muʿallima ‘the teacher’ who uses classic Karaite works and premises to teach the Hebrew Bible 12:

Among those [heretics] living in the Holy Land there was al-Sheikh Abu’l-Faraj, may his bones be committed to hell. It happened that a certain fool from Castile, named Cid Abu’l-Taras, went over and met the wicked al-Sheikh Abu’l-Faraj, who seduced him into heresy. Under the guidance of the latter, Abu’l-Taras composed a work animated by seduction and perversion, which he introduced into Castile and [by means of which] he led many astray. When Abu’l-Taras passed on to hell, he was survived by his accursed wife, whom [his adherents] used to address as al-Mu‘allima and on whom they relied for authoritative tradition. They would ask each other what Mu‘allima’s usage was, and they would follow suit. [This went on] until the rise to power of the nasi R. Joseph b. Ferruziel, surnamed Cidellus, who suppressed them even beyond their former lowly state. He drove them out of all the strongholds of Castile except for one, which he granted them, since he did not want to put them to death (inasmuch as capital punishment is not administered at the present time). However, after his death, the heretics erupted again until the reign of King Don Alfonso son of Raimund, king of kings, the Emperador. In his reign there rose nesiim who pursued the way of their fathers and suppressed the heretics [again].

These, then, are the substantial extant descriptions of the Karaite presence in medieval Iberia from the time and place. No other direct first-person evidence of the existence of this group in al-Andalus is known to exist. However, scholars have long been aware of one other document from the Genizah that contains allusions to Andalusis who emigrated to the East in the eleventh century and were forced by circumstances to practice Karaism: University of Cambridge manuscript T-S 13j9.4, which contains family and private correspondence sent from Jerusalem to Toledo in 1057 13. This particular letter has attracted the attention of the most renowned specialists in both the history of mediaeval Judaism, including Simha Assaf 14, Eliyahu Ashtor 15, Shelomo D. Goitein 16 and Moshe Gil 17, and the history of Jewish women, such as Renée Levine Melammed 18.

The author of the letter, Simon of Toledo, had settled in Jerusalem with his father and was writing to his sister, Balluta, who had stayed behind in al-Andalus. On a personal level, the letter contains a variety of details that are extremely easy to identify with, even today. Simon writes that this letter is accompanied by another one for his brother, who was living at that time in Uclés (Cuenca province), making this the first and earliest written mention of a Jewish presence in that region. This part is missing from the manuscript, which seems to confirm that it reached its recipient, although it should be borne in mind that the letter to Balluta turned up at the halfway point between the two cities, in Cairo.

In Jerusalem, Simon had entered into a happy marriage and took loving care of his disabled father. His letter expresses a great deal of interest in all the members of the family still living in Toledo, which had been stricken by a famine. He is delighted about new marriages, waxes nostalgic, even about an article of clothing he had left behind and, with characteristic wit, brings his sister up to date on all the gossip about their fellow countrymen living in Jerusalem. Particularly notable are the oldest known mention of the Jewish community in Madrid and the machinations of the Jewish women from Toledo residing in the holy city regarding their co-religionists and their relationships with the Karaites. Simon provides his sister Balluta with all sorts of detailed information about these affairs, underscoring the strong sense of camaraderie between the two siblings. Simon exerted some authority in his circle, and seems to have acted as a kind of mediator between conflicting parties. The meticulousness of his letter and the level of the writing indicate that he had received an excellent education. Balluta, in turn, seems to have been a widow and mother, although no mention is made of her husband. She was also apparently the head of what remained of the family in Toledo.

The document testifies to the terrible situation in Toledo during the first years of the reign of King al-Maʾmūn (r. 1043-1075) and contains a wealth of information about the social lives and relationships of the Andalusi Jews of the time, who found themselves forced to emigrate due to the situation produced by the fall of the Caliphate of Cordoba and the emergence of the independent taifas (1009-1031). In fact, Simon’s intention seems to be to reunite the entire family in Jerusalem very soon.

The letter also gives some inkling of the relationship between the Karaites and the Rabbinites, and how one group could be forced by circumstances to live with the other and adapt to their internal regulations. These episodes of cohabitation could even result in illicit situations, depending on the group involved:

T-S 13j9.4

|

ואמא אבראהים בן פדאנגׄ ואבראהים בן אלהרוני פוצלו אלי |

29 |

|

|

אלקדס מן בלאד אלרום בעד מחאן גׄרת עליהם כמא קד ערפתם פלמא וצל אבן |

30 |

|

|

פדאנגׄ מע זוגׄתה ובניהם עניים שבויים אלי אלרמלה קבל וצולהם אלקדס ראו אלנסי אל טליטליאת |

31 |

|

|

מן ראיהן אן יתקולו עליהם ענד אלקראין אן זוגׄתה חראם עליה פאתצל בי אלכבר |

32 |

|

|

פקצדתהן / ואקימת בדלך / קיאמתהן וחרמת / עלי מן יכשף אמרה / לעלמי אנה יקצד אל / קראין פלמא וצלו אלי / אלקדס טלעו אלי / סמרתקה ובקו מעהם / וצארו מנהם / ותעיישו בינהם / ואנזלוהם פי / דאר ועאמלוהם / באלגׄמיל פבעד / בקי בינהם נחו / סנתין כשפו / אמרה לשיוך / אלקראין וקאלו / אנה יבקא מע / זוגׄתה והי חראם / עליה עלי מדהבה[ם] / פאראדו יפר[קו] / בינהם פלמא / עלמת דלך / כאצמתהם / וגרי ביננא / כצומה / פי סבבהם / וכאן גואבי / ליעקב אן / כדאך זוגתך / חראם עליך / עלי דינך ומדהבך / אד אכדמא אכין לאכתין והו / חראם ענד אל / קראין פלמא / סמע דלך / מני פארקהא / ואפתרז מנהא |

[margin] |

|

|

תם וקפת לאדונינו אב בית דין פי סבב אלעניה אלשבויה וארסל אלי אלקראין יקול |

1 [verso] |

|

|

אנה ליס יטלקהא אלא עלי אלמדהב אלדי זוגׄהא וכתובתהא כֻתבת ענד אלרבאנין |

2 |

|

|

פיזן מהרהא וחיניד יטלקהא ולם אזל אנא אתלטף אמרה חתי קבלוה אלרבאנין |

3 |

|

|

ונזל אלי ענדהם מע זוגׄתה ואולאדה אבו זכרי ויוסף ומוסי וחלוה ואנזלוה פי דאר |

4 |

|

|

בין אלרבאנין ויעאמלוה באלגמיל ליס עגזה מעהם שי פאן ליס כאן ירידו יקבלוהם |

5 |

|

|

לסבב אן כאנו רבאנין וצארו קראין ומכתו ענדהם סנתין פלמא ראית מא אראדו |

6 |

|

|

יפעלו באלעניה יפרקוהא מן זוגהא ויבקו אלאטפאל איתאם פי אלחיאה וכאן זמאן שדה |

7 |

|

|

וגׄוע פעלת פי אמרהם מא יתיבני אללה עליה והו אלאן אבראהים אלמדכור יכרגׄ |

8 |

|

|

מע אבנה אלי צׄיעה פי אלשאם קריב מן אלקדס להמא פיהא דכאן ויתעיישו פיהא |

9 |

|

|

והם בכיר מסתורין ולא יטׄן אחד לאן להם דלאלה עלי תחרים אלאכתין בעד אל |

10 |

|

|

מות ולא יקדר אחדהם אליום מן אהל אלעלם ירי פיה וגה אכתר אן יקולו אן הכדי |

11 |

|

|

אסתסן ענן רייסהם וקדמׄוןׄ אלקׄרׄאׄין ויבהתו בשבאה לא מעול עליהא פלמא |

12 |

|

|

ראו אן אבן פדאנגׄ קד שדֿ מנהם ורגׄע אלי אלרבאנין שביה מן קאל אשובה אל אישי |

13 |

|

|

הראשון כי טוב לי אז מעתה חלו אליד ואדֿכו אלאמר עלי יעקב כשיתהם אלא |

14 |

|

|

יזול איצׄא הו מנהם ובקי מע זוגתה גיר אנה אסתחלפוה אן ינעזל מנהא אשר |

15 |

|

|

לא ציויתי ולא עלתה על לבי פערפתך יאכתי בדלך חתי תוקף אכוהא סידי מוסי |

16 |

|

|

בן אלפלמקי עלי כתאבי ולולא אן כתבת עלי חאל עגׄל אלא וכאתבתה בדלך |

17 |

|

Translation T-S 13j9.4

Regarding Ibrāhīm b. Fadānj and Ibrāhīm b. al-Harūnī, they arrived in (30) Jerusalem from the Christian lands (bilād al-rūm: Byzantium) after the suffering they endured, as you know. When Ibn (31) Fadānj arrived in Ramallah with his wife and children, poor captives, before reaching Jerusalem, the people of Toledo had (32) the bright idea of reporting them to the Karaites because his wife was forbidden to him. As soon as I received news of this [margin] I contacted them / which caused / a stir amongst them and I curse / whoever had spread word of this affair / because I/ knew that it would reach the / Karaites. When they got to / Jerusalem they went up to / Samareitike and stayed with them, / they became one of them, / they lived amongst them, / they were taken into / a home and treated / well. After / they had stayed with them for / about two years they spread / word of the affair to the Karaite authorities, asserting / that he was staying with / his wife which was forbidden / according to their doctrines. / They intended to separate / the two of them and as soon as / I found out about it / I lodged a complaint / and, amongst us, this created / a controversy / concerning them. / I responded / to Jacob like this: ‘Being / thus, your wife / she is forbidden to you / according to your regulations and doctrines / because you took two brothers for two sisters and that / is forbidden to the / Karaites’. As soon as / he heard what / I said to him, he separated from her / and divorced.

[verso] (1) I then updated our lord, the president of the court, about the poor captive woman and he sent a message to the Karaites that said (2) that he could only divorce her according to the doctrine by which he had entered into marriage with her and that his marriage certificate had been issued by the rabbis. (3) He would pay her dowry and then he would divorce her. I continued to follow the matter until the rabbis received him (4) and he stayed with them along with his wife and children, Abū Zikrī, Yosef, Mūsā and Ḥalwa. They lodged in a house (5) amongst the Rabbinites and they treated him well, they lacked for nothing and although they did not want to take them in (6) because, as Rabbinites, they had become Karaites and had stayed with them for two years. When I saw what they wanted (7) to do with the poor woman, to separate her from her husband, making the children orphans in the world, at a time of hardship (8) and famine, I did for them what God will reward me for.

Now he, the aforementioned Ibrāhīm, has gone (9) with his son to a village in the Levant, near Jerusalem where they have a shop that provides them with sustenance. (10) They are well, respected and nobody is of the opinion that there is evidence by which the two sisters are prohibited to him after (11) death. To this day, none of their specialists can offer proof that there is another possibility in his case except to affirm that this (12) was customary with Anan, their leader, and the ancient Karaites, without getting tangled up in thorn bushes that should not be torn up. When (13) they saw that Ibn Fadānj fled from them and returned to the Rabbinites, similar to he who said: I return to my first (14) husband because I was better then than now (Hosea 2:9), they slackened the rope and excused the matter of Jacob, fearing that (15) he would leave them as well. He stayed with his wife, although they took testimony from him that he would separate from her, which (16) I did not command nor did it enter my mind (Jeremiah 7:31).

I am updating you about this, my sister, so that you show his brother, my lord Mūsā (17) al-Falmiqī, my letter. If I were not writing in such an improvised manner, I would have written to tell him so.

Little more is known about Karaism in al-Andalus, despite significant attempts to reconstruct or guess at its alleged academic organon 19.

The letter that is the main focus of this study is a unique document deposited in the Cairo Genizah and currently held at Cambridge University Library (T-S 8j41.7). As far as we know, it has not attracted any prior academic attention. The text is a letter of introduction in which its author, Moses, a Sephardic Jew, declares that he has left his entire family and native land and has spent the two gold coins that he had (equivalent to eight grams). He appears to have spent some time with the Rabbinites, who according to Moses himself, treated him rather well, providing him passage on a boat going to Alexandria, where he would be able to meet up with the Karaites. Because Moses is seeking support, he does not skimp on the blessings when it comes to the Karaites to whom he is sending his missive.

The letter has a number of sections written in Hebrew, especially the blessings. Its author even goes so far as to intersperse passages from the Bible in his discourse, in the classic style of the Andalusi poets and prose writers from the golden age of Hebrew letters in al-Andalus (mid-11th to mid-12th century). The Hebrew is correct and formal. The translation presented here uses italics to denote the areas expressed in Hebrew and to differentiate them from the sections written in Judeo-Arabic.

At no time does Moses state his profession or specialty, only the religious group to which he belongs. He seems to have no resourses beyond his pen, and his command of Hebrew could be a strong indication that he worked as a secretary (kātib), with ample preparation to perform administrative work for some wealthy Jew. In fact, in the letter he demonstrates his mastery of both Arabic and Hebrew as well as his ability to insert fragments from Psalms into his Arabic writing, as in lines 8 (Psalm 66:5 נ֘וֹרָ֥א עֲ֝לִילָ֗ה עַל־בְּנֵ֥י אָדָֽם:) and 16 (Psalm 119:63 חָבֵ֣ר אָ֭נִי לְכָל־אֲשֶׁ֣ר יְרֵא֑וּךָ), to then close his letter after a long paragraph in Hebrew with Psalm 125:4 (הֵיטִ֣יבָה י֭י לַטּוֹבִ֑ים וְ֝לִֽישָׁרִ֗ים בְּלִבּוֹתָֽם:). Moses is even able to devise a truly biblical style of blessing, such as וְיַצִּילֵם מִכֹּל צַר וְאוֹיֵב וּמִכֹּל אוֹרֵב וּמְבַקֵּשׁ רָעָתָם וְיִתְּנֵם לְחֵן לְחֶסֶד וּלְרַחֲמִים בְּעֵינָיו וּבְעֵינֵי כָּל־רֹאֵיהֶם אָמֵן (lines 20-21). Moreover, Moses expresses himself in Hebrew, adopting the Andalusi technique of mixing biblical passages as if creating a mosaic with Biblical verses. For instance, line 12 uses part of 2 Chronicles 6:27 to close the sentence 20 (אֱלֹהֵי יִשְֹרָאֵל יַגְדִּיל חַסְדָּם וְיוֹרֵם אֶל־הַדֶּ֥רֶךְ הַטּוֹבָ֖ה אֲשֶׁ֣ר יֵֽלְכוּ־בָ֑הּ). He is able to repeat this same ending in a new sentence made up of parts of three verses: Nehemiah 2:8, Psalm 103:4 and 2 Chronicles 6:27 in lines 13-14, producing: כְּיַד־אֱלֹהַ֖י הַטּוֹבָ֥ה עָלָֽי: יִרְבֶּה לָהֶם חֶ֣סֶד וְרַֽחֲמִֽים: וְיוֹרֵם אֶל־הַדֶּ֥רֶךְ הַטּוֹבָ֖ה; and even four (Job 14:1, Psalm 78:49, Jeremiah 29:11 and Isaiah 30:8) in lines 22-25, introducing this long paragraph in Hebrew with a verb in Arabic: מִכָּל־צָרָה וְצוּקָה וּמִן יָגוֹן וַאֲנָחָה וְאַל יַבִיאֲכֶם לְמַתְּנַת יְדֵי אָדָם שֶׁהוּא יְל֣וּד אִשָּׁ֑ה קְצַ֥ר יָ֝מִ֗ים וּֽשְׂבַ֣ע כְּלִמָּה וְיָסֵר מֵכֶם עֶבְרָ֣ה וָזַ֣עַם וְצָרָ֑ה וְיִתֵּן לָכֶ֖ם אַֽחֲרִ֥ית וְתִקְוָֽה: לָכֶם וּלְכָל־אַחֵינוּ בְּנֵי הַמִּקְרָא וּשְׁלוֹמְכֶם כֻּלְּכֶם יִפְרֶה וְיִרְבֶּה וְיִשְֹגֵּא וְיִדְגֵּא לָעַ֖ד עַד־עוֹלָֽם: אָמֵן.

Regarding his connection to one religious group or another, in principle there is no reason to doubt his words, despite the explanations he feels compelled to give, given the difficult situations in which he found himself during his journey from al-Andalus to Egypt. Neither is there any information in the letter that makes it possible to assign a date. We are inclined to date the letter between the first half of the eleventh and first half of the twelfth centuries. There are many examples – including the one presented earlier in this work – of Andalusis who emigrated during this period to the East, fleeing the difficult economic and political circumstances in al-Andalus at the time, to settle in Egypt or the Holy Land, some with the hope of reuniting part of their family in their new home.

Edition TS 8j41.7 21

[recto]

|

יא סידי ויא שיכי וכבירי אלמדכור מרוה ומן אדאם אללה סלאמתה ואכמל כראמתה |

1 |

|

ואקי דכל צאלחה עינה בלגה 22 גאית אמלה ומנהא אר[..]גה וסו על[י]ה מא נעם לה עליה[ם] |

2 |

|

[...] מע קותה יא סידי [..] אטאל אללה בקאך 23 וכפיך [אסבא]ב אלזמאן ווקאך טול אלעליתה 24 |

3 |

|

[...] עליך פעת[...] בדן אח[...]ה [...]ר ו[...]ך עלי [...] |

4 |

|

[...] א[...]ן יא סידי אנא רגל מן אהל אלאנדלס מן מדינת ג[...]ה |

5 |

|

אגי מן א[הל אל]קראין תקררת עלי נפסי אן נ[...] אלקודס 25 עמרה אלרחמאן פי [איאמנא...] |

6 |

|

תכרגת י[...]מן ממני במא עטיה ותרכת אב ואם ואחים ואחיות וגמיע אלאעילה |

7 |

|

[...]בה כמא שא וקצ̇ה נור̇א על̇ילה ע̇ל בנ̇י אד̇ם אקול פי [...] |

8 |

|

[...] יא סידי מן גמיע מא כאן ענדי אלא דינארין פוצלת בהא [...] |

9 |

|

למא פרג מע אלגמיע ולם יתבקא שי אד אלפני נפסי באלאחתיאג אלסואל אלי בעד א[...] |

10 |

|

רבונין אד לם אסב קראים פרכבוני אלבחר תם זדוני בעד פעלהם מעי כתיר מן אלגמיל [...] |

11 |

|

ואולא עלי אסל אלהי ישרׄ יגדׄיל חסדׄם ויורׄם אׄל הדרך הטובׄה אשׄר ילכׄו בׄה תם וצלת יא סידי אלי |

12 |

|

אלאסכנדריה ועמלו מעי אהל אלאסכנדריה כתיר מן אלגמיל כיׄד אלהׄי הטוׄבה עׄלי אלהׄי עב ירבה להם |

13 |

|

חסׄד ורחמׄים ויורׄם אל הדרׄך הטובׄה תם כתבו לי אהל אלאסכנדריה אלי בעץׄ אצחאבנא 26 אלרבונין |

14 |

|

אן לא יפרטו פי ויעמלו מעי גמיל ופצׄל ואנא יא סידי לא אחב דלך אלא אן יקצה אלי אלקראים |

15 |

|

אלדי הם מן מדהבי ואעתקאדי כׄקׄ חבׄר אנׄי לכׄל אשׄר יראׄוך וגׄ ואלאן יא סידי ועזיז נפסי |

16 |

|

קצדת פצׄל אלהי ישרׄ ופצׄלכם [...] אהל אלקעד ואהל אלפצׄל ואלגמיל עס חתי ודוני |

17 |

|

בשיא מן ענד[ה]ם ותעמלו מעי חסד ואמׄת אד קד וצלני אללה בינכם ואנא קצדתכם כמא |

18 |

|

קצדת גירכם ואנת יא סידי אפעל פי הדא כמא תוגד ותתאב מן גמיל פעלך וחסן עואידך |

19 |

|

ענד סאדאתי ושיוכי אלקראים אידהם אללה ואטאל בקאהם ויציׄלם מׄכל צׄר ואויׄב ומכׄל אורב |

20 |

|

ומבקׄש רעתם ויתנׄם לחׄן ולחסׄד ולרחמׄים בעינׄיו ובעינׄי כל רואיהׄם אמׄן פאסל מן אללה |

21 |

|

לא ינזל בה אלאחתיאג ולא תדרכה אלצפאת 27 ולא תחוטה אלאקטאר 28 אן יכלצכם מכל צרה וצוקה |

22 |

|

ומ[ן יגו]ן ואנחה ואל יביאכם למתנת ידי אדם שׄהוא ילוד אשה קצר ימים ושבע כלימה |

23 |

|

ויסיר מכם עברה וזעם וצרה ויתן לכם אחרית ותקוה לכם ולכל אחינו בני המקרא ושלומכם |

24 |

|

כלכם יפרה וירבה וישגא וידגא לעד עד עולם אמן - הטיבה יי לטובים וליש[רים] בלבותם |

25 |

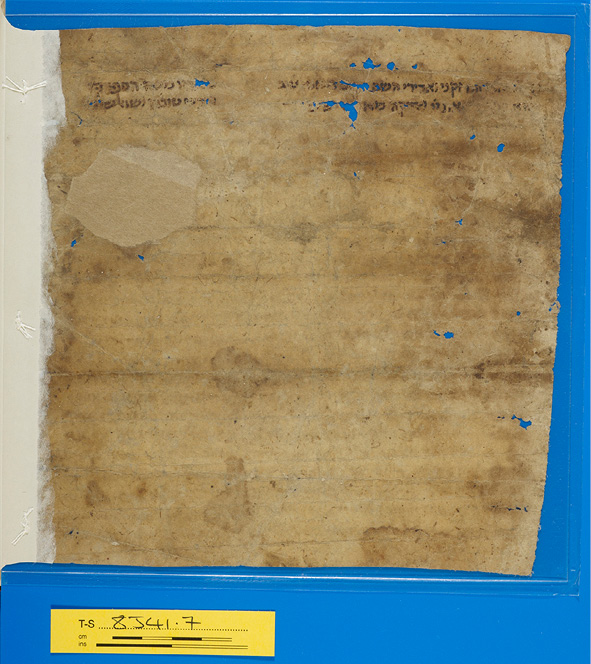

[Verso, address]

|

מאחיו משה הספרדי |

[... ... ...] זקני ואדירי השם [...] המזמן טוב |

1 |

|

דורש טובה ושואל שלום |

[ישא ברכה מאת יי וצדקה מא[להי י]שעו |

2 |

Translation T-S 8j41.7

[recto]

(1) My lord, teacher and mentor of renowned prestige, may God preserve your health, shower you with compassion, (2) grant you access to success […] and and will bring your desires fulfils, namely, […] and likewise to have that which pleases Him for them (3) […] with His force.

My lord, may God prolong your life, protect you from the vicissitudes of fate and allow you to maintain your superior status, (4) […] to you [… … … … … … …] (5) […] my lord, I am a man of the people of al-Andalus, from the city are of [G/J…] (6) I come from the Karaites and decided [to travel] to Jerusalem, May the Merciful build it [in our days …] […] (7) I left […] with what I gave him and I left behind a father, mother, brothers, sisters and the entire family (8) […] according to His will and design, He is terrible in his doing toward the children of men (Psalm 66:5).

I say in reference to […] (9) […] my lord, all I had with me was two dinars and I spent them […] (10) to accommodate everyone and I have nothing left. I got by with what I need by asking after […] (11) the rabbis because I did not renounce the Karaites, I was boarded at sea and then they treated me with all kinds of favours […] (12) and in the first place to ask the God of Israel to increase His mercy towards them and show them the right path so that they follow it. Then, my Lord, I reached (13) Alexandria and the Alexandrians treated me with all kinds of favours because the good hand of God was upon me (Nehemiah 2:8), may God increase towards them (14) His mercy and compassion and show them the right path. Then, the Alexandrians wrote about me to some of our rabbi co-religionist (15) so that they would not ignore me and would treat me with favour and grace, my Lord, I do not like that, if the Karaites are not informed (16) with whom I share customs and beliefs, as it is written I am a companion of all that fear thee (Psalm 119:63) and as it continues.

Now, my lord and beloved of the soul, (17) I ask a favour of the God of Israel and you all […] exemplary persons and illustrious and generous persons, may peace be with them, that they give me (18) something of them and you treat me with grace and favour since God has sent me amongst you. I ask you as (19) I have asked others. You, my lord, do with me in this respect as you please and as befits your good works and your good practices (20) with my lords and teachers in the Karaites, may God keep them and prolong their lives, free them from hardship, foe and machinations (21) and try to do them harm, granting them grace and favour as well as compassion in His eyes here and those who see them, amen.

I beg God (22) [Who] is not subject to need, Who cannot be captured by attributes, and Who cannot be encircled by the regions (of the world) to free them from all hardship and distress, (23) from affliction and pain, and grant them no offering from the hands of man that is born of woman, of few days and full of trouble, (24) keep you from transgression, aversion and anguish, grant them offspring and home for you and for all our Karaite brothers, keep (25) all of you safe, growing, being fruitful and multiplying and strengthened forever and ever, amen. May God bless the good and righteous of heart.

[Verso, Address] (1) […] the elders and men of great renown […] who summoned good (2) He shall receive a blessing from the LORD, and righteousness from the God of his salvation (Psalms 24:5)

His brother Moses the Sephardic Jew seeking good and appealing for peace.

1.T-S 8J41.7 (recto). Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University.

2.T-S 8J41.7 (verso). Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University.

Bibliographical References

Ashtor, Eliyahu (1964) Documentos Españoles de la Genizah. Sefarad 24, pp. 41-80.

Asín Palacios, Miguel (1984) Abenházam de Córdoba y su historia crítica de las ideas religiosas. Madrid.

Assaf, Simha (1946) Texts and Studies in Jewish History (in Hebrew). Jerusalem.

Baneth, David (1977) The Book of refutation and proof on the despised faith, the Book of the Khazars known as the Kuzari (in Hebrew). Jerusalem.

Brook, Kevin Alan (2018) The Jews of Khazaria. Lanham-Maryland. 3rd ed.

Corriente, Federico (1997) A dictionary of Andalusi Arabic. Leiden, New York.

Dozy, Reinhart (188) Supplément aux dictionnaires árabes. Leiden

Friedman, Mordechai Akiva (2013) India Book IV/A: Ḥalfon and Judah ha-Levi—the Lives of a Merchant Scholar and a Poet Laureate according to the Cairo Geniza Documents (in Hebrew). Jerusalem.

Friedman, Mordechai Akiva (2016) A Dictionary of Medieval Judeo-Arabic in the India Book Letters from the Geniza and in other Texts (in Hebrew). Jerusalem.

Gil, Moshe (1983) Palestine during the First Muslim Period (634–1099) (in Hebrew). Tel-Aviv.

Goitein, Shelomo Dov (1978) A Mediterranean Society: The Jewish Communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza, Los Angeles, Berkeley and London.

Golb, Norman; Pritsak, Omeljan (1982) Khazarian Hebrew documents of the tenth century. Ithaca, NY.

Ibn Daud (2010) Abraham ibn Daud, Sefer ha-qabbalah (The book of tradition). A critical edition with a translation and notes by Gerson D. Cohen. Philadephia.

Ibn Ḥazm (1996) Abû Muḥammad ʿAlī b. Aḥmad al-maʿrūf bi-Ibn Ḥazm al-Ẓāhirī, Al-fisal fi l-milal wa-l-ahwāʾ wa-l-niḥal, edited by Muḥammad Ibrāhīm Naṣr and ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ʿUmayra. Beirut. 2nd ed.

Khan, Geoffrey (2000) The early Karaite tradition of Hebrew grammatical thought: including a critical edition, translation and analysis of the Diqduq of uq of Yaʿqūb Yūsuf ibn Nūḥ on Hagiographa. Leiden, Boston.

Khan, Geoffrey; Gallego, María Ángeles; Olszowy-Schlanger, Judith (2003) The Karaite tradition of Hebrew grammatical thought in its classical form: a critical edition and English translation of al-Kitāb al-Kāfī fī al-luġa al-ʿIbrāniyya by Faraj Hārūn Ibn al-Faraj, 2 volumes. Leiden.

Lasker, Daniel (1992) Karaism in Twelfth-Century Spain. Journal of Jewish Thought and Philosophy 1, pp. 179-195.

Margoliouth, George (1897) Ibn Al-Hītī’s Arabic Chronicle of Karaite Doctors. The Jewish Quarterly Review 9.3, pp. 429-443.

Martínez Delgado, José (2012) La carta al rey de los Jazares y la rihla, en María José Cano Pérez y Tania Mª García Arévalo (eds.), Oriente desde Occidente: Los escritos de viajes Judíos, Cristianos y Musulmanes sobre Siria-Palestina (s. XII-XVII). Granada, volumen I, pp. 154-187.

Martínez Delgado, José; Ashur, Amir, 2021 La vida cotidiana de los judíos de Alandalús (siglos x-xii) Antología de manuscritos de la Guenizá de El Cairo (University of Cambridge). Córdoba.

Melammed, Renee Levine (2015) Spanish Women’s Lives as Reflected in the Cairo Geniza. Hispania Judaica Bulletin, Articles, Reviews, Bibliography and Manuscripts on Sefarad. Between Edom and Kedar: Studies in Memory of Yom Tov Assis. Editors: Aldina Quintana, Raquel Ibáñez-Sperber and Ram Ben-Shalom, 11, Part 2, pp. 93-108.

Nemoy, Leon de (1952) Karaite anthology: excerpts from early literature. New Haven, London.

Polliack, Meira (ed.) (2013) Karaite Judaism. A Guide to its History and Literary Sources. Leiden-Boston.

Schur, Nathan (1992) History of the Karaites. Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Bern, etc.

Vidro, Nadia (2011) Verbal Morphology in the Karaite Treatise on Hebrew Grammar Kitāb al-ʿuqūd fī taṣārīf al-luġa al-ʿibrāniyya. Leiden-Boston.

Vidro, Nadia (2013) A Medieval Karaite Pedagogical Grammar of Hebrew: A Critical Edition and English Translation of Kitāb al-ʿuqūd fī taṣārīf al-luġa al-ʿibrāniyya. Leiden-Boston.

Walfish, Barry Dov; Kizilov, Mikhail (2010) Bibliographia Karaitica. An Annotated Bibliography of Karaites and Karaism. Leiden-Boston.

1. For an introduction to Karaite Judaism, the best works are Polliack (2013); and Walfish and Kizilov (2010). See also the monograph by Schur (1992) and Nemoy (1952).

2. A significant portion of their output was collected in the acclaimed chronicle by the fifteenth-century Karaite Jew, David al-Hītī, published by Margoliouth (1897). On the contribution of this school to the study of biblical Hebrew, see Khan (2000), Khan, Gallego, Olszowy-Schlanger (2003) and Vidro (2011 and 2013).

3. On this community, see Brook (2018). On the attempts to contact with this kingdom from al-Andalus, see Golb and Pritsak (1982) and Martínez Delgado (2012).

4. See the edition by Baneth (1977).

5. Alexandria was the exit point toward the Holy Land. On May 14th 1141 Judah Halevi took the same route, see Friedman (2013: 329˗334, and especially 333).

6. Ibn Ḥazm (ed. Naṣr and ʿUmayra), 1996, volume I: 177-179.

7. In the edition: Simeon.

8. In the original, surely by mistake, ʿazīz.

9. In the edition, al-yahūd al-qarāyīn! wa-l-mayn. The section contains another variant from two other manuscript copies: al-ʿirās al-mass, which in Andalusi could mean ‘tasteless heap’, so long as it is read al-ʿiras al-mass (Corriente, 1997: 349: ʿiras ‘heap’ and p 501: mass ‘tasteless’), which could reflect a disparaging designation that was characteristic of the time and place. Miguel Asín Palacios prefers to emend al-ʿirās al-mass to rās al-ǧālūt ‘exilarch’ (Asín Palacios, 1984, Volume II: 211, note 85), which is highly appropriate given the reference to Anan, but very difficult to explain philologically, especially because of the plural antecedent suffixed to maṣḍar (wa-tasmīhum), which shows that the designation is aimed at the group and not Anan.

10. A strange word that could be interpreted from Classical Hebrew as ‘hosanna makers’. Asín Palacios hesitantly proposes the interpretation of ‘Essenes’ (Asín Palacios, 1984, Volume II p. 211, note 86). We choose to follow Dozy’s reading, which includes šaʿānīn as a corrupt form of הושענה, ‘hosanna’ (Dozy, 1881, volumen I: 765).

11. Ibn Daud (ed. Cohen), 2010: 68 in the edition and 93 in the translation: ‘we have also seen some of their descendants in Toledo, scholars who informed us that their legal practice conforms to Rabbanite usage’.

12. Ibn Daud (ed. Cohen), 2010: 69 in the edition and 94-95 in the translation.

13. Ashtor (1964). This has been thoroughly revised and translated again into Spanish in Martínez Delgado – Ashur (2021: 79-88).

14. Assaf (1946: 106˗113).

15. Ashtor (1964).

16. Goitein (1978, vol. 3: 241; vol. 6 [indices]: 176).

17. Gil (1983, vol. 3: 90˗95).

18. Levine Melammed (2015).

19. Lasker (1992: 179-195).

20. The Masoretic accentuation is reproduced here to distinguish the sections expressed in the author’s words from the biblical citations.

21. The letter is faded and damaged, and this edition should be considered as draft. We encourage the readers to suggest alternative readings or translations.

22. Ar. balagha amana, see Friedman (2016: 52)

23. See Friedman (2016: 63)

24. See Friedman (2016: 642)

25. We thank Prof. M.A. Friedman for the reading of this line, and especially the reading of the word אלקודס.

26. See Friedman (2016: 733)

27. See Friedman (2016: 217)

28. See Friedman (2016: 799)