Measuring Human “Progress” in the New Millennium: The Jewish Question Revisited

Midiendo el «progreso» humano en el Nuevo Milenio:

la Cuestión Judía revisitada

David Lempert

superlemp@yahoo.com

Recibido: 25-12-2014 | Aceptado: 2-12-2015

Abstract

This is an article in two parts. Part i offers a new way of looking at progressivism and progressive politics by defining different typologies of progressivism and by looking for these approaches in the cultural strategies of specific ethnic groups. The study offers a theory of how these progressive cultural strategies are maintained and distinguishes these strategies from apparent “progress” that may simply be a phenomenon of temporary accommodation of different ethnic groups in more complex systems. Part ii examines the ideology of “progress” as part of the cultural strategy of Jews and whether this strategy, which appears stronger when Jews are minorities in the Diaspora, is consistent with Jewish culture once Jews have a territorial boundary where they are a “majority.” This article touches upon the political choices that Jewish “political progressives” and Jews, overall, have made recently in the U.S.; modifying their support for “progress” in return for political representation, with parallels to the historical situations of other minorities. While “identity based” political choice that slows the overall “progress” of civilization appears to have protected Jewish interests in the short term, historical comparisons suggest that this choice will endanger Jews if the U.S. economy and U.S. global influence collapse, in a direct historical parallel to the European Holocaust; offering an opportunity to test theories on how (and whether) “progress” occurs. In short, this study examines the choice that Jews made in the 20th century to define themselves as “European” rather than “Middle Eastern” (or “Eastern”) and how a rethinking of this choice could be fundamental to protecting Jews in Israel and to restarting a global impetus for both social and political “progress.”

Key Words: Progressive, left, liberalism, social justice, political justice, rights, Jews, Blacks, Israel, Holocaust, U.S. Presidential elections, empire, ethnic conflict, modernization, globalization.

Resumen

Este artículo consta de dos partes. En la primera parte se ofrece un nuevo enfoque sobre el progresismo y las políticas progresistas mediante la definición de diversas tipologías de progresismo y buscando estas aproximaciones en las estrategias culturales de grupos étnicos específicos. Este trabajo teoriza sobre la forma en que estas estrategias se mantienen y las distingue del «progreso» aparente que puede ser simplemente un fenómeno efímero de adaptación de dichos grupos étnicos en sistemas más complejos. En la segunda parte se examina la ideología del «progreso» como componente en la estrategia cultural de los judíos y si esta estrategia, que se muestra más fuerte cuando los judíos son minorías en diáspora, es coherente con la cultura judía una vez los judíos han conseguido un límite territorial en el que son ya «mayoría». Este artículo alude a las opciones políticas que los judíos «políticamente progresistas» y los judíos, en general, han tomado recientemente en los Estados Unidos de América; modificando su apoyo al «progreso» a cambio de más representación política de forma paralela a las situaciones históricas de otras minorías. Aunque la opción política «basada en la identidad» que ha ralentizado el «progreso» general de la civilización parece haber protegido los intereses judíos a corto plazo, las comparaciones históricas sugieren que esta elección puede poner en peligro a los judíos si la economía estadounidense y su influencia mundial se colapsan, de manera paralela a lo que ocurrió durante el Holocausto europeo; ofreciendo una oportunidad para poner a prueba las teorías sobre cómo (y si) se produce un «progreso». En resumen, este estudio examina las elecciones tomadas por los judíos durante el siglo xx para definirse a sí mismos como «europeos» en vez de «orientales de Levante» (o «del Este») y como un replanteamiento de esta elección podría ser fundamental para la protección de los judíos en Israel reiniciando de manera global el «progreso» tanto a nivel social como político.

Palabras clave: Progresismo, izquierda, liberalismo, justicia social, justicia política, derechos, judíos, negros, Israel, holocausto, elecciones generales estadounidenses, imperio, conflicto étnico, modernización, globalización.

cómo citar este trabajo | how to cite this paper

Lempert, D. (2015), Measuring Human “Progress” in the New Millennium: The Jewish Question Revisited. Miscelánea de Estudios Árabes y Hebraicos. Sección Hebreo, 64: 93-170.

- Introduction

In an interview on the news network Democracy Now exploring U.S. government response to the global financial crisis officially starting in 2008, journalist Naomi Klein raised but did not answer a question about something she termed the “intellectual dishonesty” of “progressive” “liberal left” politics in the U.S. The answer to and the rephrasing of, that seemingly simple question may touch on the very heart of global politics and identities in this century and on the human future.

At the center of the discussion was why economist Larry Summers, whose name is associated with the causes of the global financial crisis, along with Robert Rubin and Alan Greenspan, have all escaped accountability or (as in the case of Summers) were even “rehired” to preside over the “solutions.” Klein charged that the world was “paying the price of the—frankly, the intellectual dishonesty of the progressive liberal left during the Bush years,”1 though not defining who constitutes this group or why they would have chosen dishonesty.

Has the “progressive liberal left” been “intellectually dishonest?” Who are they? What dishonesty is being referred to? Is there a particular double standard that is being applied? And what does this question about one such group in the U.S. at one historical time in history tell us about the much larger question about human “progress”?

While terms like “progressive,” “liberal,” and “left” are often in the eye of the beholder, it is possible to more precisely define different approaches to “progress” (ideas and actions) and to link them to particular cultural traditions to see whether or not they are part of the human experience that is transmitted through time. Once the traditions are identified with certain ethnic groups, it is possible to measure some of the non-conformist (“progressive”) behaviors of those identified groups over time and to look at the decisions that these groups are now making that do have implications for historical progress. These decisions can also be used as a way to examine and test some ideas about historical change, with unfolding events in our own time serving as a kind of social experiment on “progress.”

It is possible to use available data on minorities in the U.S. – African Americans, Hispanics, and particularly Jews – to confirm Klein’s observation while posing questions and seeking data that take the analysis several steps farther. The historical data of changing voting patterns of Jews in the U.S., for instance, indicates a co-optation of their historic progressive role in supporting equal application of laws and standards over the past century (some four to five generations). While Jews in the U.S. retain cultural differences and avoid full assimilation, Jewish intellectuals have recently diverged from an historic practice of supporting ideals of rule of law in democratic systems where Jews are a minority2. The oft offered explanation that this double standard represents the “protection of Israel” raises a larger question of how Jewish “progressives” are defining their interests and their role and the political trade Jews are making. It also raises questions about whether a single minority culture continues to promote strategies of human “progress” once its own interests seem protected and when it has something to protect that it fears to lose.

A closer look at the data suggests that non-Jewish leaders have managed to co-opt Jewish progressives by playing on Jewish fears and short-term interests now in the post-Cold War period in much the same way as during the beginning of the Cold War. The significance of this choice for the U.S. and for the world, given the important role that Jews played in promoting “progress” between 1945 and 1980, is that it has severely weakened any political force or pressure for global progress towards ideals of legality, co-existence, symmetry and rule of law. It is possible that this change signals the “end” of history in our lifetimes, in the sense of regression towards short-term self-interest and political power rather than development of law and standards3.

As Jews in the U.S. agreed to redefine themselves as “American/Western European” and “anti-Eastern European” for security at the beginning of the Cold War, Israel’s Jews have also continued to consider themselves “Europeans” in the European colonial tradition, rather than seek to diversify the Jewish global identity in a way that more closely ingratiates Jews with their Middle Eastern, Asian, or African neighbours. The identity of Jews in the U.S. and throughout the world, today, is one that includes little identification with Middle Eastern neighbors or Asians and that continues to ally with U.S. and European imperial and resource interests.

Comparison of the Jewish situation in the world today with that of Jews in the collapsing Austro-Hungarian and German Empires in World War i suggests that the conditions prior to the Holocaust could now be re-emerging as the U.S. Empire collapses. This very choice that Jews have made to secure their interests could actually be what most endangers the Jewish future. As the U.S. Empire and Western European influence continue to fall and as oil resources in the Middle East are exhausted, Jews will soon face a new dilemma over identity as well as a potential resurgence of violence directed against Jews in the United States in ways that will test theories about Jewish culture and progress, about progress, and about ethnic accommodation and violence.

There is an emerging new opportunity for Jews in Israel and elsewhere to redefine themselves by reconnecting with Middle Eastern roots and attempting a new peace, reconciliation, and prosperity alongside Middle Eastern neighbors, the emerging powers of Asia, and the Islamic world, but Jews do not appear to be taking it4. That choice and its consequences also offer a living social experiment on cultural adaptation and on “progress.”

- Part i: Measuring “Progress” in the New Millennium and its Ethnic Dimensions

The first part of this article begins the search for answers about human political and social progress by looking for ways to measure it and to link it to social science variables. It begins with a new way of looking at such progressivism and progressive politics that defines different typologies of progressivism and looks for these approaches in the cultural strategies of specific ethnic groups. Data on political behavior among different minority groups helps to generate some theories as to how progressive cultural strategies are maintained and how they can be distinguished from apparent “progress” that may simply be the temporary accommodation of different ethnic groups in more complex systems.

- Defining “Progressive” Development of Humanity

Is civilization still progressing or are we regressing? How would we even know? Answering this question requires starting with an agreed definition on what constitutes human progress, but there does not seem to be a clear or agreed definition of what “progressive” politics is. The ideal itself seems to be a different battleground for ethnic and cultural interpretations. Nevertheless, definitions seem to fall into three categories, even though there is disagreement about their exact origins or motivating forces. Each category also offers some potential measures.

Human “progress” and “progressivism” is generally conceived in three ways that are not mutually exclusive. Each offers measures that can also be used to differentiate political platforms, ideologies, candidates, and actions over time:

- Technological “Modernization” Progressives

Technocrats and modernists focus on industrial and technological development, with the measure of progress the understanding of and application of natural and scientific laws to achieve greater human control over the universe. This reflects the biological reality of human and primate evolutions of the brain that allow for understanding of time and the ability to develop technologies. There is some debate over whether this is entirely a linear process of development or a radial adaptive process of developing science and technology in environments and how that relates to the other two types of progress; social and political. The Western concept of science generally assumes a linear, though uneven progress5. Sometimes the social and political institutions that accompany these technologies are also assumed to be those that are the most advanced and progressive6. Though few civilizations have produced advanced technology without also developing philosophies that have included concepts of human progress (some form of social and political equality), there are also questions as to whether industrial advance can be achieved without some kind of competition either between ethnic groups (with the need for military dominance driving innovation) or between individuals.

Measures: Scientific and productivity advances.

- Social Progressives

Social progressives focus on equitable results (equality of condition) following principles of symmetry and concepts of “justice” or “fairness” that follow from that principle. One of their key aims is “progressive taxation” as a way of redistributing wealth and offering economic opportunity and a safety net. This view of progress is a religious or social and economic rights concept that comes out of almost every religious tradition and embraces the ideal of charity and giving a helping hand to others. It is said to reflect the biological impulse of humans for social relations and cooperation, starting with small collectives. In larger societies, the ideal is often reflected in “interest” politics for meeting the needs of minorities and the poor through social justice.

Measures: Economic and social justice for the poor or for minorities that suffer discrimination. The key measures of political action and candidate stands are those on: “Progressive taxation” and redistribution for social welfare (health care and education, social services) and economic opportunity; military and police spending for defensive protection rather than for hegemony over resources or peoples; subsidies for farmers and rural areas.

- “Rule of Law” and Political Progressives and Civil Libertarians

Political progressives focus on development of human systems, institutions and instruments, usually based on the concept of “rule of law” or “natural rights” in order to enforce the principles of symmetry and diversity for long-term survival interests. This is the political rights view of equity and justice that looks not only at outcomes and charitable acts but that tries to systematize the process to assure balances of interests and appropriate long-term results (including protections for future generations). It is the “meta” approach to progress that combines scientific thinking and long-term planning with concepts of social justice and continued scientific development. The biological root of the idea of political progress is the evolution of the human ability both to plan for future events and to demonstrate empathy. It is a counterweight to the idea of “might makes right” and that individual nations or individuals are “exceptional” or “above the law.” In complex societies, this idea of progress goes beyond the idea of efficiency and modern bureaucracy to incorporate an ideal of accountability, participation, fairness (equal opportunity) and rights (both individual rights and community/cultural rights) at different levels in ways that are enforceable. This systematization also assumes the use of scientific thinking to establish standards and measurements of the quality of processes.

Measures: Political participation and oversight to achieve equality (e.g., political system reform for equal access and oversight; corporate regulation; governmental regulations; electoral reforms; legal system participation and reforms; press and agenda setting equality of access): Judicial equity and equal enforcement (including use of mechanisms against high officials in government and corporate/private sector); International law and treaty obligations; Civil liberties (reduction of death penalty and torture; protection of privacy; due process and protection against collective punishment or discrimination; gender rights; protection of future generation interests and environment; etc.); Rule of law for protection of the full set of political rights (consumer rights, labor rights; Indigenous rights ad federalism); Adherence of individual nations to international legal bodies rather than avoidance through ideologies of “exceptionalism” or special rules. Another way to measure progress in this area is the advance of social science since inquiry into human systems and the creation and testing of those systems in a scientific way (combining the ideals of technical progress and of social justice) reflect the higher order development of planning systems. One set of measures that the author has generated from these concepts that reflects the post-World War ii international consensus found in international is a set of “Universal Development Goals”7.

Before trying to link these concepts to specific ethnic groups, it is interesting to take a quick look at the three categories to consider where they might be historically rooted. Any “civilization” by definition supports the concept of technological progress. Today, the ideology of “development” or the “right to development” as promoted by international powers is generally defined by these interests as the promotion of technological advance using the science and technologies of these powerful interests.

The idea of “social justice” is rooted in most major religions and is not specific to any group. In complex systems, it is often the rallying point for any categorically disadvantaged minority. Much of the global movement today for equality between “North and South” or for promotion of the Millennium Development Goals (now the Sustainable Development Goals) through the United Nations, is one where social progressives can come from multiple groups. Though there are differences in the attention on “social justice” in the constitutions and rhetoric of “socialist” countries of Asia and Eastern and Northern Europe, versus the Anglo-American countries, the idea of social justice seems partly related to ethnic factors (and climate, and geography that may underlie them)8 and partly to the kind of ethnic competition that exists within a complex system.

While the “political justice” and “rule of law” approach can be traced to many civilizations, going back to the first legal codes and to the development of international commerce, it is also particularly associated with societies and subcultures that have developed complex legal and literate traditions.

- Measuring “Progressive” Politics Against Some Real Variables: Rephrasing the Question to Include Ethnicity

Who are the “Progressives”? Are they random groups that arise spontaneously with a social function of protecting interests and to keeping certain types of societies moving “forward” or are progressives a defined functional group (like healers or spiritual leaders) whose existence and effectiveness can be correlated over time to measure historical “progress”? Do “progressives” only arise when societies confront difficulties and need to re-adapt to their environments to improve survival, or do complex societies create and protect a specific role for “progressives” within systems like education, religion, leadership, and communications? Given the changes in the roles of these institutions in contemporary societies, there are real questions as to whether or not there is a “natural” social role that humans have developed to promote long-term “progress” that goes beyond simple “stability” and continuity. However, if progress is measured in human societies over the past several generations, there seems to be a correlation between “progress” and the activity of particular minority groups. For political progressives (the third category above) in many societies today, there seems to be a clear correlation with Jews, while for social progressives (the second category above), any disadvantaged minority can fit that role. By looking at behaviors of ethnic groups, it is possible to develop some basic theories to try to measure how societies progress technologically, socially, and politically, and what the future might hold.

The place to start a search for a baseline on “progressives” is to look at the characteristics of people who support progressive causes and to separate those “progressives” who arise spontaneously within a system in order to change it for their individual interests and those whose characteristics are larger and unchanging. While political analysis is often defined by labeling that can hide the underlying alliances and actions of identifiable groups, one way to get around this dilemma is to look for these harder variables (more stable affiliations) and to move political analysis closer to anthropology and sociology, using quantifiable measures of age, gender, race and (though not entirely clear cut) ethnicity. That means taking euphemistic words such as “left” or “liberal” or “progressive” and trying to fill them in with categories such as ethnicity or age or class in order to understand what may really be going on in progressive decisions and modeling this over time.

In fact, there is some positive correlation between the different progressive agendas (technological, social, and political) and different ethnic groups. While there is a larger question as to whether ethnic groups spontaneously move to take on these roles due simply to factors of position or size, and to fulfill a certain social function in complex systems over time, it makes sense to start with a smaller question as to whether there are any identifiable cultural groups in our own time with these roles and to see how they redefine and change those roles over time.

The question that Klein asks is really a “shadow” question that can be analyzed by looking at specific ethnic groups; particularly Jews. Klein is identifying contradictions in the behavior of political progressives; the third “type” of progressive identified in the section above, whom she and the media have called “the liberal left.” The intellectual dishonesty that she detects consists of the willingness to accept a double standard for an unidentified reason. Since the mission of political progressives is to apply standards equally to all and to look for solutions that are systemic, she seeks an explanation as to the underlying causes that have led to the violation of this mission by people who previously expressed a strong support for it.

The way to turn the question about the “liberal left” into a question about Jewish political behavior is to use a simple anthropological trick. Anthropologists ask whether there is a fear or taboo of using a more descriptive word for the “liberal left” that is being hidden by a euphemism. If there is such a taboo, this underlying fear might also explain why the group might sometimes resort to breaking its own standards. To find out, we simply try out substitute words for “liberal left” or for other characteristics of individuals mentioned in the question or who are raising the question. We can also look for a parallel question to Klein’s question to confirm a starting point for this analysis and to relate it to a larger phenomenon. Here’s how.

In addition to Klein’s question about economic policy and specific individuals who have supported that policy at high levels, authors and journalists who have been defined as “progressives” of this “liberal left” (including Klein and Democracy Now) also pose a very similar question about military policy and international law. On issues such as use of the U.S. military or the support for foreign military actions in violations of international law and treaty agreements, they also raise questions about the unwillingness of the same “progressives” to enforce politically progressive standards on people such as former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, who was also rehired as part of the Democratic Presidential transition, and on former Assistant Secretary of State, Richard Holbrooke, who has been rehired as special envoy to Afghanistan and Pakistan. Their assumption is that progressives should have been much more vocal and consistent during the “Bush years.” That question can be situated in time to date back more than three decades to 1980 and earlier, before members of the Bush family served as U.S. President or Vice President.

To derive a social scientific question that closely fits the problem, we can substitute the phrase “political non-conformist (independent) Jews” for “liberal left” in Klein’s question and the parallel question, above. The newly formed question is now striking and direct.

Why is it that “politically non-conformist” (“independent”) Jews are “intellectually dishonest” (substituting some other goal for their long-held principles of rule of law and political progress) when it comes to blaming or holding accountable people like Summers, Rubin, Greenspan, Holbrooke (who are all Jewish), and Albright, (who was born Jewish)?

Without assuming whether Klein’s world view is right or wrong, it is easy to simply rephrase her question for at least one potential and important group of political progressives, in this way:

Why have many Jews agreed to support stagnation in or reversal of global social and political justice while politically non-conformist Jews whose previous role was to push the world towards objective standards, have been turning away from upholding those standards?

This may be the real unanswered question that was right in front of Ms. Klein’s and her interviewer’s (Amy Goodman’s) noses. Both are Jewish.

Similar substitutions can be tried using other ethnic groups to ask some similar questions about both political and social progress.

- Opening a Window into the Larger Question of “Progress” by Examining the Political Behaviors of Jews and the Strategy of Political Progress in the Culture of Diaspora Jews

The identification of Jews as one important component of the “progressive left” makes it possible to measure one of the potential driving forces of “political progress” by examining how Jewish culture promotes and protects (or how it compromises or abandons) this strategy under different conditions. By examining how Jewish political behavior is changing overall and the size of “progressives” as a subset of the Jewish minority population over time, it is possible to come up with some conclusions about whether “progress” is specifically linked to cultures or whether it is only linked to the relative vulnerability of certain minority cultures at different points in time. The answer to this question has implications for overall human progress, for other minority groups, and also for Jews. The assumption here is that using Jews as an indicator of progressive politics makes some logical sense and is a good fit. Moreover, although it is not a perfect fit, since the identification of “Jews” or any racial, ethnic, or minority group is also socially constructed, it is a relatively stable category over time and offers a good starting point.

By contrast to movements for social progress that are rooted in most major religions and are not specific to Jews (even though Jews have long been associated with movements for social justice through labor and political movements in the U.S. and Europe), the category of political progress is often associated with Jews today9 and is one that offers itself to measurement (of quantity of effort, though the actual quality can be subject to dispute). While there is a debate as to whether this third concept of progress (of history moving towards some “ends” rather than repeating itself in cycles) is even a Jewish “invention,” there is a core Jewish philosophy of “tikkun olam;” of perfecting institutions through law as well as a part of Jewish identity that reinforces survival against the forces of empires through legal and moral challenges to those empires. A central distinguishing idea in the Jewish religion is one that humans control destiny, not outside forces. According to this philosophy, Jews create meaning not only through ritual activity, as in other cultures, but in this activity of mending the world or perfecting the world. For Jews living in the Diaspora for 2,000 years, the essential definitions of perfecting the world have included the protection of small minority peoples and their chosen identities through concepts of rights (including rights to a “Sabbath” day each week free from labor and to the worship of one’s ancestors and God) and codified law (Commandments) within these larger systems. For the past century in the West, Jews have been over-represented in modern legal professions and have been a driving force in promoting concepts of civil liberties, rights, and protections through law and institutional frameworks that are central to the concept of political “progressivism”10.

Jews have historically represented a significant part of political non-conformist intellectuals and activists promoting a particular view about human and civilization’s progress and how individual decisions can be part of such progress.

As a (Jewish) progressive, Klein expresses concern that (Jewish) political progressives are abandoning their agenda and her observation can be tested with hard evidence. Assuming that a certain group of political progressives can be identified (and evidence in the next section suggests that Jews do fit this category and that Klein is observing a real change), it is possible to try to explain the change. Her worry suggests a belief that (Jewish) progressives are making a deliberate (and harmful) free choice. Jews (previously a political progressive group) aren’t assimilating but are abandoning progressive traditions without any clear cause. Why would Jews give up an established cultural belief that society apparently defines in a positive way (as “progressive”)?

Klein has put her finger on a key issue of both overall political progress and Jewish political identity that has at its roots some key decisions of how Jews in the world are now collectively interpreting their (our) survival interests and their (our11) alliances. If Jews are giving up the ideal of political progress because they are on a path to assimilation, this suggests that there is really no such thing as “political progress”; that it is only a ruse used by certain minority groups to promote their assimilation and that it will be given up once they feel relatively secure. Similarly, if Jews are giving up the ideal of political progress out of fear for survival (or a combination of relative security and some ultimate fear), can the idea of political progress ever really take root in human societies, or is it also subject to elimination through manipulation of fear? Given the position of Jews in the world today, how Jews are making this decision not only has an impact on U.S. and Middle Eastern politics, but on several concerns for the future of humanity and global survival in what many futurists describe as a post-oil, desertifying, resource depleted world, where the U.S. Empire is crumbling and where Asian and other power centers are emerging, without any particular minority group rooted in these traditions.

Does political progress require the existence of a particular group with a particular “politically progressive” tradition in order for the progress to continue, and if so, what happens when it give it up? Is political progressivism something that is “cultural” and specific to part of a once victimized minority group such as Jews that is independent of economic victimization? Can an ethnic group that initiates a progressive agenda that includes both social and political progressive features continue to support this agenda after the group is no longer disadvantaged? Or, does human “political progress” require continued victimization of a group to create the impetus for change (making it almost paradoxically impossible for real “progress” to be continued and sustainable)? If neither condition exists, is human progress really possible?

- Progress or Regress?: Evidence of Recent Regressive Behavior of Minorities and “Progressives” in U.S. Elections to Generate Hypotheses about Ethnicity and “Progress”

It is relatively easy to generate data demonstrating the disappearance of support for political or social progress in the U.S. between 1980 and 2012. What is compelling about this general data is not only how strong the trend in the U.S. over the past (more than a generation) has been showing the decline of “progressivism” but also how closely it follows ethnic lines and how at least one group in the U.S. (Muslims) is becoming more progressive. Changes seem to be related to the political and economic positions of those groups; with Jews and Muslims moving in opposite directions in progressive politics. Assuming the high education and political activity of Jews, the data on Jews is particularly intriguing. Overall, the findings offer a way not only for individuals to reconsider the basis of their own political behaviors and what they have chosen to give up, but to alert different ethnic groups as to what they stand for (if anything other than self-protection).

Most political scientists examine political data to measure the changing support for different coalitions over time but do not try to measure “progress” over time or support for “progress” among particular ethnic groups. While there is no reliable measure or poll of the absolute numbers of “progressives” in the three different categories of progressives identified above, it is possible to use some shadow measures to explore some trends and begin to offer hypotheses with polling data that does ask about ethnicity.

In the United States, one place to start is with support for candidates in Presidential primaries (and particularly in the Democratic primaries) where activists more directly express their preferences than in Presidential votes. Recently, the creation of a “Progressive caucus” in the U.S. Congress also offers a way to look at one self-defined group and their characteristics. Some comparisons between the voting for Congress, in Presidential primaries and in Presidential elections also offer a window into the decisions that these “progressives” are making.

General data for elections in the United States for the past 35 years (now more than a generation and possibly long enough to confirm a trend) tends to confirm both that there is a general trend away from social and political progressivism among the very same people who were progressive before, and that Jews in particular are weaker than ever as political progressives. A longer look at data for Jewish “progressive” voting also shows this shift even more strongly in ways that tend to confirm that (Jewish) progressives have been making some kind of bargain that is counter to their previous progressive stance. Added to this, it would be interesting to measure if there is a trend away from science and technological progress globally (and a case might be made that there has) that could also be confirmed through other measures such as spending and dedication to pure science and the range of support to applied science and technology.

- The General Trend

One way to look at progressive politics is to start by looking at national votes within the Democratic Party for the past 35 years. Although there can be “progressives” in any political party, and some Republicans (among them some libertarians and some professionals building standards on spending) take some “progressive” stances in line with the three types identified above, all current members of Congress’ “Progressive Caucus” are Democrats and the full range of issues that fit the definition of “progressive” has recently been associated with the Democratic Party. The way to look at the trends is to take candidate voting records and position and to hold them against the measures of “social progressive” (second type) and “political progressive” (third type) to determine which candidates fit the definition, then to see how much initial support they received in primary elections.

While historical interpretation introduces biases and the classification categories are imperfect, I have made some very rough interpretations of candidates for the past nine elections, putting candidates and their votes into three categories: non-progressive, progressive (including those candidates who are or were members of the Congressional Progressive Caucus since 1991 or whose records were similar) and a third “unclear” category. Of course, the classifications and data itself is rough, since not all candidates stay until the end of Presidential primaries, some votes are tallied in caucuses, not all candidates appear on each ballot, and so on. Support for globalization or for particular U.S. military intervention is also hard to interpret (is it for resources and control or for promoting rights and progress?). However, the data does offer an opportunity to put some numbers on an often-stated belief that in the U.S. there has been a major shift away from Progressive politics and that today’s “Democratic Party” candidates may be even more conservative (non-progressive) than even Republican Party candidates used to be more than a generation ago.

Other ways of conducting the analysis result in similar conclusions, including comparing political platforms or stresses of particular issues in campaign speeches12. The purpose of the brief overview is just to set an initial baseline.

This table cannot suggest whether this phenomenon – the severe downward trend in progressivism, if correctly interpreted – is part of a “cycle” or the end of “progress”, and it is only for the United States. However, it is a first measure that can be viewed in an historical context with more data for specific ethnic groups.

Table 1: Downward Trends in Progressive Voting in Democratic Primaries13

|

1980 |

1984 |

1988 |

1992 |

1996 |

2000 |

2004 |

2008 |

2012 |

|

|

Candidates Tagged as Non-Progressive Caucus |

La Rouche |

Glenn, La Rouche |

Gore, Gephardt |

Clinton, La Rouche |

Clinton, La Rouche |

Gore |

Kerry, Edwards, Gephardt, Lieberman, Graham |

Obama, Clinton, Richardson, Biden, Dodd, Edwards |

Obama |

|

Unclear |

Carter Unpledged |

Mondale Hart |

Dukakis (42); Hart |

Tsongas (18%), Kerrey (2%) |

- |

Bradley (20%) |

Clarke (3%) |

- |

- |

|

Candidate Tagged as Progressive |

Kennedy (38%), Brown |

Jesse Jackson (18%); McGovern (2%) |

Jesse Jackson (29%); Simon (6%) |

Brown (20%), Harkin (1%); McCarthy, Agran (1%) |

None |

? |

Kucinich (4%), Sharpton (2%), Dean (5%) |

Kucinich, Gravel |

No challenge |

|

Progressive and Unclear Primary Vote |

99% |

94% |

79% |

42% |

Incumbent |

20% |

14% |

2% |

0% |

|

Progressive Primary Vote |

41% |

20% |

35% |

22% |

Incumbent |

? |

11% |

<2% |

0% |

- Jewish Progressives Over Time

The more interesting trend, also downward, is that of the “independent” party voting of Jews in the U.S. for most of the past century. If “non-conformist” Jews do represent the political progressives, their voting patterns would indicate that either the culture has been changed or that they are making the kind of hypocritical choice that Klein identifies. While there is no way of knowing how many Jews are “progressive” or which categories of “progressive” they fall into, there are clear records of their Presidential electoral voting for the two “Progressive” parties that directly chose this name in 1924 and 1948 as well as for a social progressive party (the “Socialist” Party) in 1920, and whose political agendas reflected the goals of social justice and/or political progress. In more recent elections, it is possible to track Jewish support for candidates who represented progressive agendas of the Green Party that included social progressive and politically progressive agendas (including one Green Party candidate, Cynthia McKinney, who was a member of the Congressional Progressive Caucus).

Table 2. Politically Non-Conformist (Independent/”Progressive”) Jewish Voting in U.S. Presidential Elections

|

Candidate(s) |

Party Label |

Year |

Jewish Vote1 |

Popular Vote2 |

Jews as a Percentage3 |

|

Eugene Debs |

Socialist |

1920 |

38% |

3% |

62% |

|

Robert La Follette, Sr. |

Progressive |

1924 |

22% |

17% |

7% |

|

Henry Wallace |

Progressive |

1948 |

15% |

2% |

31% |

|

John Anderson Barry Commoner |

Independent Citizens |

1980 |

14% |

7% |

10% |

|

Ross Perot |

Independent |

1992 |

9% |

19% |

2% |

|

Ralph Nader |

Green |

2000 |

1% |

3% |

2% |

|

Ralph Nader |

Green |

2004 |

1% |

1% |

5% |

|

Ralph Nader Cynthia McKinney |

Independent Green |

2008 |

0.5% |

1% |

5% |

|

Jill Stein4 |

Green |

2012 |

<1% |

0.3% |

? |

|

1. Jewish voting data (percentages) is from: L. Sandy Maisel and Ira Forman, Eds., Jews in American Politics, 2001. on the web at: http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/US-Israel/jewvote.html 2. The national voting data used for comparisons is drawn from published sources including Wikipedia articles on each election. 3. The assumption is that Jews are 4-5% of the vote; roughly double that of other groups. The Jewish tradition is one of active civic participation (making fate rather than accepting fate) and Jewish voter turnouts are high, while the average voter turnout in Presidential elections is between 40 and 60%. Bernard Avishai, “Obama’s Jews,” Harper’s, October 2008, page 9. Note that my calculations are rough given the overall imprecision of the data. For more specific figures, I would have to use the Jewish population of the country in each election year and also look at the exact voter turnout in each year. 4. Exit polls showed 69% of Jews voted for Obama and 30% for Romney with 1% unclear, even though the Green Party candidate, Jill Stein, was Jewish. There is some possibility that this data was skewed and that Jewish vote was higher but that Stein was simply excluded from the polling. Two “swing state” results were Ohio: 64 (or 69, depending on the poll):31.5: and 4.5 not explained; and Florida: 66 (or 68): 30: and 4 not explained. Even if the third party vote is suppressed in the media polls and was 4-4.5% in these states and maybe double that in non-swing states, it’s still way below past third party levels. However, it would suggest that a larger percent of the small vote for Jill Stein was from Jews. Stone, Andrea (2012). “Jewish Vote Goes 69% for Barack Obama: Exit Polls,” Huffington Post, posted November 7. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/11/07/jewish-voter-exit-polls_n_2084008.html |

|||||

Presidential votes in general elections are harder to use to show the specific strength of progressives, but they also reveal a startling pattern. In U.S. general elections for President, in what many have called the U.S. two-party “duopoly” system, choices have often become “strategic” votes where groups make bargains with the major Party candidates. Thus, actually votes may not directly reflect the numbers of progressives given that some progressives may have extracted promises from major party candidates in return for their votes. The ability to bargain effectively could be masking changes in progressive choices. What makes the table below so interesting is that it identifies elections where progressive Jews chose to vote strongly for the Third Party candidates, rather than put faith in bargain with one of the two major Parties.

There is no way to know the actual thinking of Jewish progressives in making these votes; whether they felt their Third Party votes were important in moving the overall political debate (for political progress) and/or in protecting Jewish progressive as a recognized bloc (social progress for Jews). Following the 1920 and 1924 votes, the Democratic Party did become progressive under Roosevelt, for example. Following 1948, however, Jews were heavily targeted in the McCarthy era purges. Yet, there is still a clear pattern in the votes.

What is important to see in the table is that Jews had a tradition of voting for Third Parties and not blindly identifying with the Democratic Party (part of the recent common wisdom). They apparently did use their voting power strategically for Third Parties, not just between the two major parties. Moreover, they made up large parts of the vote for the Socialists in 1920 and for Henry Wallace’s Progressive Party (against the Cold War) in 1948. They were also significant in 1980 in support for John Anderson, an anti-war candidate. Yet, more recently, they have fallen behind other groups in their Third Party voting.

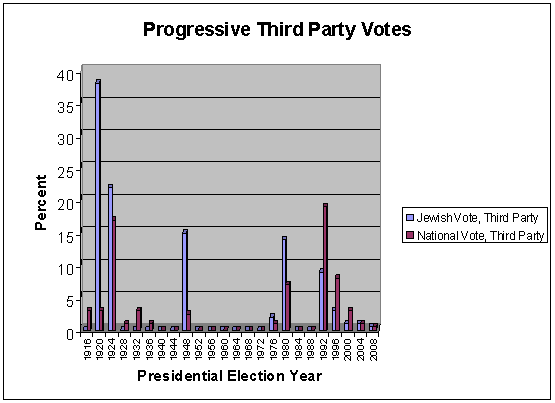

Graphing the data shows the phenomenon more clearly.

Figure 1. The “Disappearance” of Jewish Progressives

Since 1980, Jews have made a clear switch. The data might or might not indicate a general progression of Jewish voting that could suggest some kind of assimilation. But it could just as easily suggest that voting (and “assimilation”) represents a specific political choice of alliances that would confirm Klein’s observation that Jewish progressives are acting against their stated principles.

- The Congressional “Progressive Caucus” and Ethnicity

Ethnicity figures for the U.S., for the U.S. Congress and for the U.S. Congressional “Progressive Caucus” offer general information about ethnic groups and “progressive” choices on a more national level, and also suggests that Jews are becoming less progressive. While Congressional voting in the U.S. is by district and its members do not clearly reflect progressive sentiment of minorities, there is a rough correlation.

While the U.S. Congressional “Progressive caucus” has only existed since 1991 and data cannot be used to show any real trends, its membership itself offers some clues on ethnic lines as well as on issue choices of what currently constitutes “progressive” politics and also of the relative role that Jews and other ethnic groups play in it.

Below is a chart for a recent Progressive Caucus for which data were available (in office for 2007 and 2008) with tabulations of Congressional membership by ethnicity. Note that all of the members of the Caucus are members of the Democratic Party.

The interesting numbers in the table are those that suggest that progressives are probably social progressives representing the interests of disadvantaged minorities since the composition of the group is higher than that of minorities who are “disadvantaged.” Blacks make up almost half of the caucus and Blacks, Hispanics, Jews, and Asians are 62% of the members. Moreover, of Blacks in Congress, some 61% are members of the Caucus compared to 13% of all members of Congress.

Table 3. Analysis of the U.S. Congressional Progressive Caucus, 110th Congress,

by Ethnicity14

|

Ethnic Group5 |

Number of Members in Congress (Both Houses) |

Number of Democratic Party (or Independent) Members |

Number of Members in Caucus |

Percentage of Democratic Party (or Independent) Members in Caucus |

Percentage of Total Group in Caucus |

Percentage of Total Caucus |

|

Blacks |

44 |

44 |

27 |

61% |

61% |

38% |

|

Hispanics |

29 |

23 |

8 |

35% |

28% |

11% |

|

Jews |

44 |

42 |

7 |

17% |

16% |

10% |

|

Asians |

7 |

7 |

2 |

29% |

29% |

3% |

|

Other |

314 |

162 |

27 |

17% |

9% |

38% |

|

Total (including non-voting members) |

538 |

278 |

71 |

26% |

13% |

100% |

|

5. These minority groups account, overall for 30+% of the national population (Blacks at 12.3%; Hispanic at 12.5%; Jews at 2-3%; Asians at 3.6%). 2000 Census data. U.S. Bureau of the Census, “Population Profile of the U.S., 2000,” reported on the web at: |

||||||

The statistic for Jews is also interesting. Only 16% of Jewish members of Congress are now members of the Progressive Caucus; not much higher than the percentage for non-minority members (9%). Among Democrats, Jewish members of the caucus are in the same percentage as non-minority Democrats. It looks as if Jews who might otherwise be “progressive” had made a bargain with the mainstream Democrats.

- The Disappearance of Progressive Agendas in Politics Among Most Minority Groups, Throughout the Political Process: Minority Progressives Making Some Kind of Compromises or Surrender of their Agenda in 2008, Apparently for Identity Politics

The recent choice of Jewish progressive voters to support the Democratic Party candidate in Presidential elections, rather than to give support to progressive Third party candidates is reflected by the behavior of several minority groups, even in primary elections, suggesting that not only are progressives NOT using bargaining power when they do vote in the general elections, but also they are generally abandoning progressive stands overall. The way to see this is to combine data from U.S. Presidential primaries with the self-definition of “progressive” by those members of Congress who were Presidential candidates in primaries. It seems that progressives are no longer voting on issues but are seeking protection by voting for candidates who are from their ethnicity or who will choose staff from members of that ethnic group, no matter what their political preferences are.

Table 4. Projected Support in Voting if the Public Supported the Progressive Caucus’s Presidential Candidates in the 2008 Democratic Primaries

|

Ethnic Group |

Percentage of Overall Democratic Party Affiliation, Estimated by Voter Turnout and Democratic Vote in 20086 |

Percentage of Democratic Party (or Independent) Members in Progressive Caucus |

Percentage of Democratic Primary Votes for Caucus Members: Kucinich and other “Progressives” not in Congress (Gravel) |

Percentage of Democratic Primary Votes for Non-Caucus Members: Obama, Clinton, Edwards, Biden, Dodd, Richardson |

|

Blacks |

23% |

61% |

0 to 9% |

91 to 100% |

|

Hispanics |

6% |

35% |

0 to 33% |

67 to 100% |

|

Jews |

2% |

17% |

0 to 100% |

0 to 100% |

|

Total7 |

31% |

26% |

<2% |

98+% |

|

6. CNN Exit Polls, November 4, 2008, reported on the web at: http://edition.cnn.com/ELECTION/2008/results/polls/#val=USP00p1 Data is then repercentaged over 53%, the total Democratic vote. 7. Unsourced data presented in Wikipedia, “Democratic Party (U.S.) Presidential Primaries 2008, |

||||

With the basic data on minorities and “progressive” voting, as represented by the above data for the Congressional Progressive Caucus, it is possible to take a look at national voting behavior among these groups in 2008, both in the Presidential primaries where activists are more likely to vote their interests in hoping that they can influence a nominee and policies, and in the general election. What is interesting about the 2008 elections is that there were candidates who were members of the Progressive Caucus (including Dennis Kucinich and Cynthia McKinney) running against several candidates who were clearly not members of the Caucus. Barack Obama, for instance, is among the minority of Blacks in Congress who did not identify with the Progressive Caucus.

Overall, while 26% of the country’s Democrats were members of the Congressional Progressive caucus, their candidates received less than 2% of the primary votes.

There is not enough data to know exactly how individual ethnic groups voted. Progressive candidates report that they did not have the funds to do this kind of polling15. At best, it is only possible to make mathematic estimates and for smaller groups like Jews, it is impossible to see anything. But for Blacks and partly for Hispanics, the data is clear. Progressives did not vote their political views in the primaries.

Black progressives apparently voted for a Black non-progressive candidate in large numbers (Obama) because he was Black. Hispanics may have voted in larger numbers for the non-progressive Hispanic candidate, Richardson. It looks as if progressives bargained away their interests on the basis of some other definition of their interest or a co-optation of those interests in the primaries. The data here on Jewish progressives is too small, but the same questions about their choice can start to be raised, partly on the basis of where Jewish money went if not Jewish votes16.

The same phenomenon is also visible in the election, itself, where Congresswoman McKinney, a Black Progressive Caucus member, was pitted against non-member Obama.

Apparently, progressive members of different minority groups were not voting on issues but were making a strategic decision to ally with non-progressives. The progressive vote almost entirely disappeared.

One can raise questions about why the “progressive” vote for Congress is so different than that in the Presidential election process and whether there is a belief that Congress, itself, and its progressives, can pressure a President. There is also a question of whether the Congressional data is really a valid representation of “progressives.” The question that Klein is raising suggests that Congressional progressives, very much like national progressive voters, may have also made deals once they were in office, to support (or to look the other way at) activities of their non-progressive colleagues and of Presidential staff, and their appointments to high positions. This data does not offer clues as to why progressives seem to have chosen to make deals, and what interests they think they are protecting by making deals that suggest an inconsistency in their beliefs. This question that can be taken up using a different approach, in the second part of this article.

Before trying to understand why “progressives” have agreed to suppress or abandon or trade their agenda, it is important to ask whether there are any progressive minority voter groups who apparently chose not to make such a deal and to ask what might be different about them. In fact, there is one. The only minority that did not make this bargain with non-progressives, was American Muslims.

Table 5. Projected Support in Voting if the Public Supported the Caucus’s Candidates in the 2008 National Elections for President

|

Ethnic Group |

Percentage of 2008 Voters8 |

Percentage of Progressive Caucus of National Representatives |

Percentage of National Votes for Caucus Members9: McKinney |

Percentage of National Votes for Other “Progressives”: Nader/Gonzalez |

Percentage of National Votes for Non-Caucus Members: Obama |

|

Blacks |

13% |

61% |

1.0% (Combined) |

95% |

|

|

Hispanics |

9% |

28% |

< 2.0% (Combined) |

67% |

|

|

Jews |

2% |

16% |

0.5% (Combined) |

78% |

|

|

Total |

100% |

13% |

0.2% |

0.5% |

52% |

|

8. CNN Exit Polls, November 4, 2008. Note that the Jewish vote is only reported at 2% when sources generally find Jews voting at about 4-5% of the electorate. Given that there was a 62% turnout, Jews could have been overrepresented by 50+ if they all voted, pushing their share to 4+%. CNN reported an “Other” category of religions of 6% that may include some of the Jewish voters if they did, indeed, vote in large numbers in the election. 9. CNN Exit Polls, November 4, 2008, supra. |

|||||

- American Muslims: Minority Progressives Not Making the Bargain

Of all minority groups in the U.S., the one that appears to be more progressive while other groups are less progressive, is Muslims. The question is why, and the answer suggests that they are also acting on the basis of identity politics in protecting their interests. What seems to make them different is that they are one of the groups that the Democratic Party does not seem to welcome into its coalition.

There is very little data on the Muslim and Arab-American vote, given their small size, although their vote may actually be as large as that for Jews17. But there are surveys of their voting behavior in 2000 and 2004 when they suddenly moved from a standard U.S. voting pattern including support for Republicans, to the left. There is a good explanation for why. This was a group who, while not “disadvantaged” economically in the U.S., was suddenly a victim of discrimination and civil liberties violations as a result of U.S. policy regarding the Muslim world. Many had a direct interest in supporting the civil liberties agenda of political progressives as a way to protect themselves.

Using some available data, it is possible to see that they voted strongly for Ralph Nader, a political progressive candidate in the 2000, 2004 and 2008 Presidential elections who is not Muslim but is Arab-American and who spoke out as a defender of Arab-American and Muslim civil liberties. Assuming that Muslim Americans are 3% of the electorate, their votes for Nader would have accounted for about 0.6 of the national vote which was 20% of the Nader vote in 2000 but almost all of it in 2004 and 2008. This table also explains why Nader did so well in states like Michigan. It wasn’t just blue collar voters and auto workers supporting him. It was the Arab and Muslim minority there.

Table 6. Muslim-American Vote in Recent Presidential Elections18

|

Year |

Republican |

Democrat |

Nader |

|

2000 |

8% |

72% |

19% |

|

2004 (Polls) |

2% |

54% |

26% |

|

/Repercentaged |

2% |

67% |

32% |

This is not to say that there are no Muslims or Arab Americans welcomed in the Democratic Party, but simply an analysis of specific voting behaviors19.

- Part ii: Progressivism and the Current “Jewish Question”

A standard explanation of U.S. (and global) political behavior in recent times that suggests the weakening of progressive movements, even in the face of growing economic inequalities, attributes the change to both the increasing power and sophistication of control mechanisms (including media and propaganda) by elite actors. Yet, that explanation seems to fail, not only because it denies the underlying assumption that people make rational choices that reflect their interests but because it does not recognize a competing trend of increasing knowledge and cynicism among citizens as well as easier access to alternative sources of information and communications. An analysis based on rational choice suggests that progressives were making a rational choice to suppress their agenda and to deaden movements for progress. The rest of this study, focusing on Jews but applying to other groups, argues that the choice is really one being made out of fear and perceived self interest. The araticle also seeks to project these choices to logical conclusions that are startling (and horrifying) for the future of Jews, of humanity, and for concepts of “progress.”

What the U.S. Presidential election results in 2008, analyzed above, suggest is the fact that minority voters, who are most likely to be progressive, were making choices based on identity politics rather than on political agendas. (Given the incumbency of Barack Obama, 2008 is used as a clearer base year for analysis.) There is evidence that politicians can co-opt progressive segments by their own ethnicity or by the filling of positions of people with that ethnicity, regardless of whether or not they share that agenda; symbolic tokenism as convincing people they are represented or that they, too, can win the lottery. The larger question is, why minorities would want to agree to this given that majority populations apparently feel free to support candidates who represent their interests even though they are from minority groups. Moreover, why is it that progressives, who are arguably more educated and ideological than others, agree to this choice? While the 2008 electoral results raise some questions about Black progressives and their allegiances, the rest of this article focuses on Jewish progressives and their choices over the past several decades in the U.S. and outside of the U.S. Others can deal with the implications of this for Black progressives in the U.S. since a study of Jews should have similar implications for Blacks and other minorities.

Even if elites have been using money and media to drive progressives out of politics, this would still not fully explain why progressives, themselves, have long been convinced by the messages. One would still have to examine the messages and arguments that have been used to convince progressives to make concessions to support different agendas in order to understand their beliefs.

Underlying this question are assumptions about how history and progress work and how groups and cultures make decisions and changes that are too complicated to fully address in this article. Social scientists, themselves, are split into whether they think choices are rational and based on perception of self-interest or irrational and manipulated by advertising, fears, shallow appeals, or even on how “self-interest” is defined and understood in the brain. For arguments sake, the rest of the article assumes that Jewish progressives are thoughtful actors in their voting and other political behaviors and that even their motivations based on fear are part of some underlying rational or logic of self interest. Another important assumption for measuring behavior and attitudes towards progress is the fact that rational choices are being made in an environment where the very context in which choices are made is relatively constant over time and that people are aware of that context20.

It is important to also accept a frame of analysis for measuring history and to assume that history is a process that individuals affect by aggregate choices on their interests and how they define those interests, and that this is a conscious choice by individuals, added up into a collective choice. That is different from looking at human choices as driven by a collective consciousness of larger forces that drive decisions beyond individual conscious choice. Those who look at history from a macro-view in long sweeps of time for the rise and fall of civilizations, including this author in other work21, could see the same data and the story it tells as just part of a larger process and might assume the insignificance of human action and decisions22. Even though it may be difficult to link individual behaviors to collective social changes and to work on these two levels at the same time, this article assumes that there is some consistency between these levels.

Progressives themselves assume that ideas count and that philosophies and human choice move history. At the very least, the rest of this piece tests progressives’ own assumptions when applied to their choices to see whether their own choices solely reflect rational survival interests or whether progressives also perceive choices between longer term and short term interests of humanity and of their own group definition (i.e., Jewish progressives as wedded to a strategy of promoting political progress) and act in that way23.

The rest of the article examines these issues by looking at the context in which Jews make political choices and what these choices reflect. The overall question is whether Jews are visibly (consciously or subconsciously) sacrificing progressive politics for identity politics or some other short-term tradeoff, and whether this trade can be measured and explained. The piece then examines the long-term implications for Jews, themselves of this choice and whether Jews, themselves are conscious of the real implications of the short-term tradeoff they have made, given that similar tradeoffs in recent memory have been associated with genocide against the Jews when empires Jews have allied with have failed and when progressive resistance was weak. There is also a striking parallel to this choice – this “Jewish Question” – that Jews have made in the Middle East. An understanding of that choice helps to challenge much of the common wisdom and myth about Israel’s position in the world today. Finally, the changing power relations in the world today offers an opportunity to test Jewish choices, Jewish progressive politics, and the future of progressive politics overall in human history.

- The “Jewish Question” and Its Theoretical Implications: Are Jews Assimilating and Agreeing to An End to Progress or Are they Just Making a Temporary Bargain?:

Since there is enough evidence to suggest that Jews as a political group are not assimilating in the U.S. in ways that would make them indistinguishable from the mainstream, why is it that they appear to be turning away from progressive politics? Are Jews assimilating in some other way that is causing them to turn away from progressive politics to simply protect themselves, indicating that Jews24 neither really were nor will they continue to be a culture that is politically progressive? If they are not assimilating, are Jews in the U.S. simply making some short-term (possibly misguided) decisions for protection that are conflicting with other values? This question of assimilation and/or making some kind of alliance for self (group) protection is the essence of the “Jewish Question”25 (a survival strategy in relation to the powers that be). It is also a key to understanding whether a cultural strategy for political progress is independent of the conditions of a small ethnic group or whether it is simply a mechanism for self-protection that is discarded once conditions of that group improve. Given that the Jewish re-establishment of a nation state and the rise of Jews in the U.S. and other countries to a position of economic and professional status have occurred in less than the past century, there is not enough data yet to offer a clear answer. However, there could be enough data in the next few decades to provide one given that it is at least clear that Jews have sacrificed progressive politics in the short term. Putting these decisions directly in social context, to understand the logic of the choices (the Jewish answers to the “Jewish Question”) and the potential consequences, points the way to measure continuing changes and what they mean.

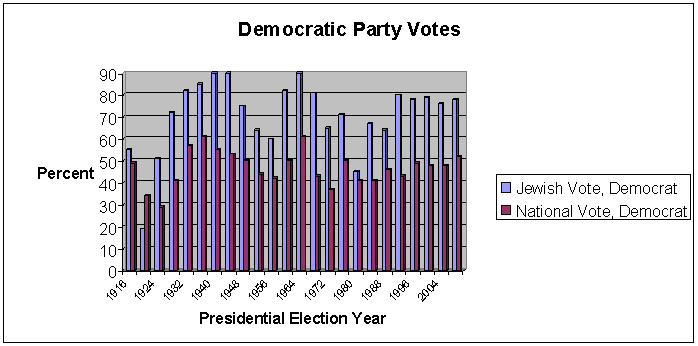

The evidence that Jews are retaining some cultural difference in the U.S., other than just a religious preference now that they have given up “traditional” or identifying dress, grooming, and language, is in their distinct set of political preferences that reflects a cultural choice rather than simply economics. While many Jews are as wealthy as most American conservative elites, they still do not vote with conservatives. While data above described Jewish voting patterns in the U.S. over much of the past century for Third Party (progressive) candidates in Presidential elections and suggested a trend towards assimilation, Jewish voters have not assimilated. The rest of the same data set, highlighting the Jewish vote for the Democratic Party and comparing it to national voting in the U.S., shows that Jewish voting has also been consistent over time. The Jewish vote for the Democratic Party is higher than that of the general population or they historically break off from the Democratic Party to vote for Progressive candidates who challenge the Party (up until the past 25 years). This pattern has held remarkably constant although there was a small shift in the 2012 election (not shown on the chart) with 69% for the Democratic candidate.

Figure 2. Consistency of Jewish Political Identification with the Democratic Party and Lack of Overall Political Assimilation

While there is a question as to whether the whole “political spectrum” in the U.S. and elsewhere shifts as all minorities assimilate into urban culture and/or assume similar economic position and status as other groups, there is still continued immigration to the U.S. and Western European countries. This is part of an arguably continuing process of cheap labor exploitation or brain drain where Jews continue to form coalitions with new minority entrants and groups who are more easily identifiable as minorities.

Those who survey the specific views of Jews, beyond their electoral choices, also find that Jews remain more progressive on both issues of social justice and political justice/ civil liberties, than the population overall and the Democratic Party. For instance, 70% of Jews rejected the Iraq war as early as 200526, although they continued to support candidates who voted for it or funded it.

- Defining the “Jewish Question”

The “Jewish Question” – the question that Jews as a minority group have always had to ask – is how they would define themselves in relation to the majority group and to its enemies. Anthropologists generally write about identity as not only a set of distinguishing traits of a group but also as a way of setting boundaries and distinguishing a relationship to others (to “the other”). While the standard question about Jews is whether they are “assimilating,” the real human choice is not between becoming one thing or another but about positioning oneself and one’s group between different groups; particularly between those who are defined as “allies” or “friends” and those who become “enemies” or “others.” In the U.S., the question about “assimilating” is not about becoming some inexact and undefined part of the U.S. elite, Christian, culture, but about how a group defines itself in relation to all of the other minorities inside the country (blacks, Native peoples, Latin Americans, Asians, and Middle Easterners) and to those outside the country.

In every country that Jews have lived, they have had to define the traits of the majority culture that they would adopt as their own and others that they would keep, and to think about how this positioned themselves as a group for survival of the group given the potential for future internal strife in the country and future invasions and wars outside of the country. Identity is partly self-defined and groups decide to stress certain traits or symbols not only to reinforce their own systems but to remind themselves of where they differ from other groups and whom their allies should be. For Jews in a Europe that was often divided between Christians and Muslims (the Moors and the Turks) or between West and East (the Slavs or migrating peoples from Asia and the Caucuses), between landed and nomadic peoples, Jews defined themselves in relation to these lines of conflict between the majority peoples, seeking to secure their status by picking winners and losers. Divisions between neighboring countries in conflict were also problematic and required Jews to choose. At times of invasions or repelling of invasions and the rise and fall of empires (invasion and overthrow of the Turks, for example), Jewish survival was dependent on how they were perceived by both sides of the conflict.

Indeed, much of the basis of Jewish identity as “politically progressive” can also be described as part of how Jews defined themselves as a minority people with a small area of resources, seeking to survive in a world of empires; the Babylonians, the Egyptians, the Romans, the Greeks, up to the Russian and U.S. Empires of our day. The creation of an identity as politically progressive was based on the ideal of a small group able to maintain its sense of differences and to survive the rise and fall of empires around them, in league with other small groups seeking to do the same.

Karl Marx’s answer to the question of Jewish identities that he posed in his own writings, was to try to create a new kind of assimilation through homogenization and destruction of all identities. It was an assimilation that was socially progressive but that largely avoided political and legal systematization. It didn’t work particularly well to protect Jewish ideals or Jews, themselves. Among those who were purged in the 1930s in a backlash to the failures of this system as it was applied in the Soviet Union were the many Jews in the Communist Party and in the State apparatus who tried to override traditional Russian culture and create a new identity27. Many of the Jews who survived are now in the U.S. and Israel where they have had to ask the “Jewish Question” again to define what their new identity would be and how they would establish new alliances.

Apparently, Jewish progressives in the U.S. have made a trade, agreeing to support U.S. elites and to avoid criticism or standards. That bargain has required accepting the definition of the U.S.’s enemies and sharing the spoils without asking too many questions. It would only be logical that the amount by which progressives have agreed to silence would be in some direct relationship to their benefit (and embarrassment) and/or in direct relationship to their feelings of insecurity (making the value of the benefit seem to be greater). Logically, then, it would seem that if Jewish political progressives have been silent it is because they perceive themselves as increasingly insecure.

- The Trade That Progressive Jews Have Made: Explaining the “Intellectual Dishonesty”:

The first part of this paper presented a chart of Jewish “progressive” voting in U.S. progressive elections, showing very strong Third Party progressive votes in 1920 and 1924, then in 1948, then in 1980. While the overall progression looks like a “trend,” these three peaks could be explained as something else. It could be that Jewish progressives were acting independently at those three times because they were not yet forced to make a “choice” to support a set of political elites. Between 1928 and 1944, the Jews in the U.S. were faced with a choice of being independent or joining with elites during a time of economic crisis and the European Holocaust. Between 1952 and 1976, they were forced to make alliances during the Cold War. After the Cold War, since 1984, there has been a new choice. One way of understanding the suppression of Jewish political progressives is to look at the “Jewish Question;” the fears and choices that Jews faced in the U.S. for self protection during the Cold War, the current “War on Terrorism” (against countries that are largely Muslim) and the deep fears and concerns that might motivate these choices and that go beyond the standard explanation that it is merely to “protect Israel”. After examining the real historical choices, it is possible to retell the history of Jewish politics and progressive choices through the prism of identity politics and self-protection.

There seems to be a common wisdom in U.S. political analysis based on the fact that Jews have largely defined their activism in relation to Israel and protections for Israel as a homeland. But from an economic and military standpoint, Israel has been much stronger, safer and more secure in the past 30 years than in its first 30 years, and that assessment would largely be true even without the military support that it receives from the U.S.28. If that is so, the real insecurity that Jews in the U.S. perceive, and that has driven them to support elites in the U.S., more likely comes from fears they have in the U.S.

This perspective reverses the view of the role of Israel in the political activity of Jews in the U.S. The politics and activism of Jews in the U.S. is not driven out of concerns for protection of Israel, given that Israel is now largely in a position to protect itself. The choice that U.S. Jews have made is one of supporting U.S. military interests in relation to their sense of their own security, and rationalizing this as the protection of Israel and of all Jews.

In an earlier article, more than a decade ago, on the Cold War29, I drew direct attention to one form of intellectual dishonesty of Jewish intellectuals that began in the 1950s and carried through to the 1980s; the willingness to fictionalize much of 20th century Russian history in order to serve the interests of American elites in the Cold War and to boost their own careers by doing so. Now that the Cold War is over and U.S. elites have defined a new “enemy” and a new “war” (or set of wars) to further their interests, there appears to be another set of deceptions to which many Jews in the U.S. have joined to further their careers. Moreover, the rewards are now greater, earning Jews not only middle class success but also positions high in the political establishment. Nevertheless, it seems that Jews (and other minorities) feel no more secure today in the post-Cold War U.S. than they were during the Cold War, or at least feel that they now have more to protect and are equally vulnerable. The pressures that led Jews to violate their professional integrity in order to boost their position during the Cold War seems to be the same calculus that now drives the politics of progressive Jews, in general.

- The Jewish Question and Progressive Politics During the Cold War